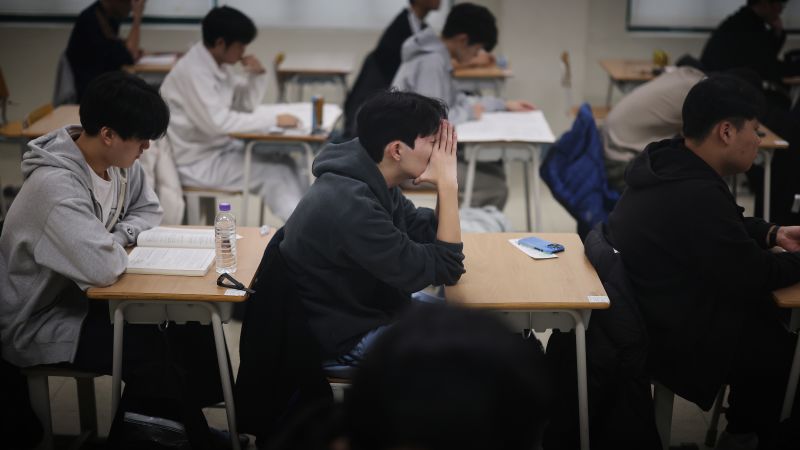

Just imagine. You are a Korean teenager taking the infamous eight-hour long college entrance exam. You have been preparing for this for months or even years. When you get to the English part, you’ll see something like this:

If you think this is difficult, how about something like this?

These are among the problems faced by students during this November’s exams (locally known as Sunun), which sparked protests so intense that the exam body’s chief executive resigned last week, according to public broadcaster KBS.

The testing agency formally apologized earlier this month, saying, “We take seriously the criticism that the difficulty level of the English portion was not appropriate.”

“We deeply apologize for causing worry to test takers and their parents,” the group said in a statement, adding that administrators would consult with schools to “resolve the question within the scope of school education.”

But many angry students and parents say the apology is not enough to make up for the damage to test scores and university entrance exams, seen as the key to future success in competitive South Korea.

Only about 3% of test takers achieved the top score in the English language section, the lowest since the new scoring system was introduced in 2018, the testing agency said.

“The former evaluation director admitted his fault when resigning,” one online user named Choi wrote on Suneun’s website. “Isn’t it common sense to consider measures for the victims, such as examinees and their guardians?”

“How can a survey of what to do for next year’s entrance exams console students who are depressed this year?”

Sunun has long been famous for its difficulty and the intense pressure it places on teenagers. For many, the race for education begins before they can even speak, with parents competing to secure a coveted spot in an elite kindergarten.

When they become middle school and high school students, they often go straight from regular classes to an after-school cram school called “Hagwon,” where their days are often centered around studying until late at night. The families hope that all this hard work will help them secure admission to top universities and give them an edge in an equally cutthroat job market.

Not just families, but the entire country takes this exam seriously.

On November 13, as more than 500,000 students nationwide sat in Sunun, all plane takeoffs and landings nationwide were prohibited for 30 minutes to prevent noise distractions during the listening section. Financial markets opened an hour late and police were called in to ensure candidates arrived at the exam center on time.

But there are dangers in such competitive testing. Testing is often seen as both a symptom and a contributor to wealth inequality, as wealthier students have access to more resources that can be advantageous.

Illegal markets are also involved. According to Yonhap News, police booked 126 people earlier this year on suspicion of selling Sunneung’s questions to hagwons and private tutors.

The heavy burden on students is often blamed for the country’s poor mental health, which had the highest suicide rate of any OECD country in 2020, according to the latest figures available.

This may also have an impact on the country’s rapidly declining birthrate.

Experts believe that the staggering cost of tuition is a major factor behind South Koreans’ reluctance to have children, along with the burden of long working hours, stagnant wages, and prohibitively high housing costs.

The government is trying to crack down on hagwon equally and lower the difficulty of entrance exams.

It has been announced that in 2023, the so-called “killer question” will be removed from Sunuun. The questions sometimes included content not covered in the public school curriculum, which the education minister at the time argued gave an unfair advantage to those who could afford private tutoring.

But apparently, even the remaining questions may be too many.

“So angry,” a commenter named Jung wrote on the testing agency’s website. “What are you going to do with your children’s lives?”

CNN’s Marianna Kim contributed to this report