Iran is living through one of the most dangerous periods in its post-revolutionary history. Protests across the country are not temporary, but sustained. A new wave of unrest is spreading across the country and violence is escalating. The true number of deaths has not yet been confirmed.

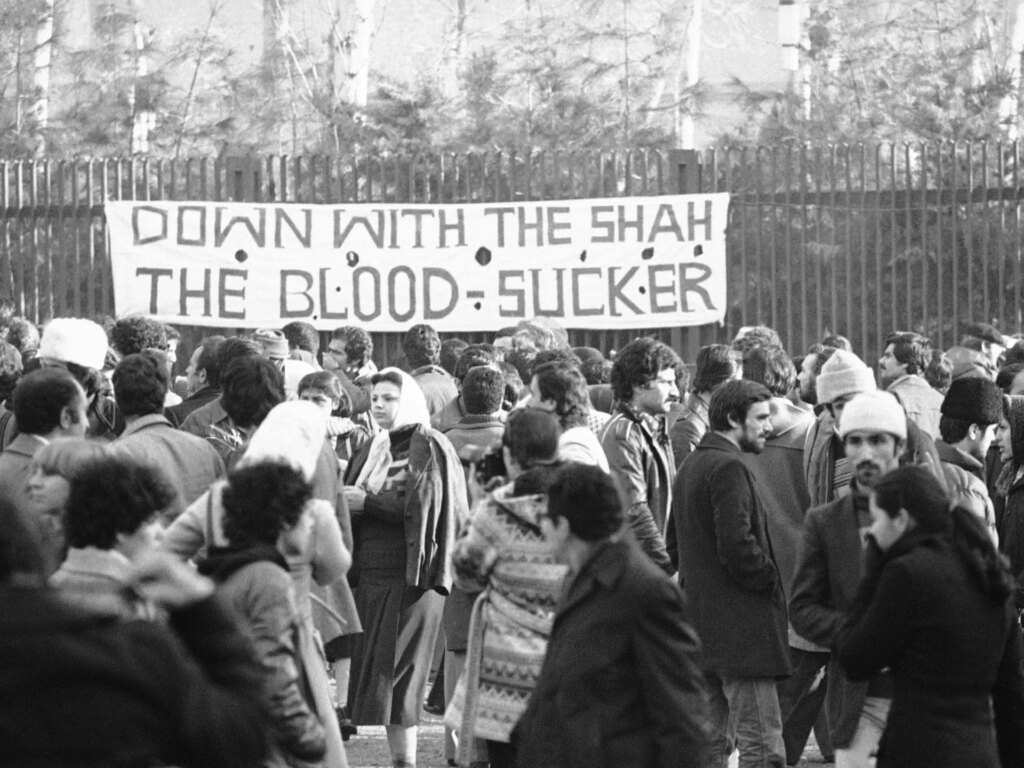

These events have reignited the familiar question of whether Iran is moving toward a new 1979.

It’s no wonder we want to rely on this analogy. Images of mass mobilizations and rapidly recurring protests are reminiscent of the final months of the Shah’s rule. However, this comparison is ultimately misleading.

The success of the 1979 revolution cannot be explained solely by mass mobilization. Rather, its victory was ensured by the mobilization of a concerted opposition under Ruhollah Khomeini and, more crucially, by the failure of the ruling elite to effectively suppress dissent.

Mohammad Reza Shah had cancer, was taking a large amount of medication, and was clearly indecisive. His leadership stalled during the crisis. He left the country twice during political upheavals, once in 1953 after being challenged by Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, and again in January 1979 when protests spread across the country.

Equally important, the shah’s repressive apparatus was fragmented and socially heterogeneous. Apart from the Shah’s central intelligence organization, SAVAK, the police and gendarmerie were tasked with maintaining social order, but the Iranian military focused more on territorial defense than political repression.

These institutions lacked systematic ideological vetting and drew personnel from diverse social and ideological backgrounds. When the shah left the country, some police forces abandoned repressive tactics and cooperated with protesters to maintain order, but military leaders hesitated in favor of self-preservation and ultimately abandoned the monarchy.

The situation today is fundamentally different. Unlike the Shah, Khamenei’s leadership shows no hesitation or indecision in times of crisis.

Since assuming the position of Supreme Leader in 1989, Khamenei has overseen a major transformation of the Islamic Republic into what I describe as a theocratic security state that relies on repression rather than social consent. As supreme leader, he presides over a highly institutionalized, cohesive, ideologically committed, and deeply invested coercive apparatus. This structural reality defines not only national sentiment but also the limits of revolutionary change in Iran today.

Coercive power in the Islamic Republic is not concentrated in a single institution. Instead, they are distributed across overlapping organizations with redundant chains of command. These forces are concentrated in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, Basij, police, intelligence services, and their attached social networks.

Iran’s coercive institutions are controlled by the regime’s die-hard supporters. Their loyalty is not just transactional. It is ideological, institutional and generational. Through ideological screening and patronage, their loyalty is not only enforced but actively cultivated.

Their social mobility, economic security, and sense of identity are tied to the survival of the regime and Khamenei’s leadership. For them, regime collapse is not a political transition. It’s an existential threat. In moments of crisis, these allies take preemptive action to prevent the spread of protests, orchestrate riots as foreign-backed incitements, and lower barriers to domestic violence.

Therefore, even if the protests were larger and more geographically widespread than the 1979 protests, they would not pose a fundamental challenge to the regime. Rather, it will lead to even harsher repression. This highlights an important lesson: protests themselves do not cause revolutions.

Revolutions occur when popular unrest intersects with elite paralysis or defection. That happened in 1979, but it’s not happening now.

It is not only protests but also direct shocks to the regime’s leadership that can change this balance. External intervention, particularly by the United States, is likely to be aimed at disrupting elite coordination by targeting high-ranking political and security officials with strikes.

Such an approach will only cause a real regime crisis if it removes Khamenei himself. Power in the Islamic Republic is highly concentrated within the ranks of the supreme leader and his inner circle. His sudden absence could spark a conflict among elites over who should succeed him, weakening cohesion at the top.

However, intervention may also strengthen supporter solidarity. If Khamenei survives, his core supporters in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the Basij, and the intelligence services will almost certainly close ranks, as they have done in previous foreign conflicts. Under these circumstances, the possibility of elite defection remains low.

Even if the regime were to collapse, Iran would not face the institutional vacuum seen in some post-intervention countries. The country’s modern bureaucracy, which has maintained continuity since the early 20th century, will continue to function in the short term. Administrative collapse will be constrained by state capacity, social organization, and national identity.

Some warn that the collapse of the Islamic Republic will inevitably lead to a prolonged insurgency. That risk cannot be ignored. However, unlike in Iraq and Afghanistan, there will be no external state actors in Iran willing and able to fund, organize, and sustain armed extremist movements. Iranian society also shows strong resistance to religious extremism and political radicalism. There is a possibility that instability after the collapse of the regime will be suppressed.

The real danger, then, is not that Iran is on the verge of a repeat of 1979, but that the persistent reliance on that analogy blinds policymakers to how the Islamic Republic functions today. Misreading the nature of Iranian power does not improve the chances of peaceful change. This increases the likelihood that Iranians themselves will bear the costs of repression, escalation, and prolonged uncertainty.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of Al Jazeera.