Editor’s note: The new series “New Orleans: The Soul of a City” explores the many ways the city intersects with history through music, food, sports and tradition, revealing how, 20 years after Katrina, New Orleans is louder and more resilient than ever. The series airs Sundays at 10pm ET/PT.

new orleans

—

– When you meet a local in the Bywater, they might offer you a matcha latte from Petit Clouet Cafe. Or visit Chance in Hell Snoballs, where you can find frozen treats in wild flavors like dill pickle, ube, and root beer.

Petit Clouet is pale yellow. The SnoBall shop is painted electric pink. There’s no escaping color and creativity here, whether literal or figurative. In a colorful and creative city, Bywater stands out.

This 120-block riverside neighborhood near the French Quarter has a great arts scene, dynamic menu, significant architecture, and a linear river park.

It is also the home of growing pains. Like many cool neighborhoods, this one was discovered. The working-class haven is partially gentrified.

Before Hurricane Katrina, Bywater was a primarily African-American family neighborhood. Since then, rents have increased. Airbnb exploded here, and for a time, affordable housing for permanent residents dried up, until short-term rental restrictions began. There is currently a major real estate development underway that threatens to change this storied neighborhood, and some would argue, for the better. Some are even worse.

For now, Bywater remains a walkable, wonderful, and unique New Orleans neighborhood worth visiting and supporting.

As a local, here’s what I would suggest:

Let’s take a walk first. There are more than 2,000 buildings, ranging from Greek Revival to Victorian styles. However, the predominant housing styles are Creole cottages, dating from 1840 to 1870, and small shotguns, dating to the 1880s.

For an authentic tour, local guide Glennis Waterman, who volunteers with Friends of the Cabildo, a nonprofit organization that supports the Louisiana State Museum, can help.

“In the early 1800s, this land was prime because of its proximity to the river, and there were several small plantations,” Waterman says of the area east of the French Quarter, past the Marigny River.

Two of the oldest buildings she stopped at outdoors are 631 Independence Street, part of the Makarty Plantation, and the restored Lombard Houses in Chartres and Bartholomew. Built in 1826, Lombard House is one of the finest examples of Norman trusses (a complex type of roof structure) and architecture of the once-prosperous West Indies.

By the mid-19th century, European immigrants, Spanish Creoles, and free people of color had arrived.

“Bywater was called Little Saxony because of the large German population,” continues Waterman.

On the city map, it became the 9th Ward in 1852, and in 1919, with the arrival of industrial canals, it was separated from the Lower 9 Wards and further designated as the Upper 9 Wards.

“There was a local competition in the 1940s,” Waterman explains why it is now called Bywater. “A student suggested the name. It was a telephone exchange when someone dialed into the switchboard.”

Green spaces and independent artistry

During the Progressive Era of the early 1900s, industrial expansion led to more wharves, railroad lines, and factories. But after World War II, these industrial sites lost their manufacturing tenants as more people moved to the suburbs. Many were abandoned, and by the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, they were plagued by blight, especially near water.

“The entire area along the river was a land of abandoned, self-destructing wharves,” says Amanda Rivera, a senior associate and architect at Esq. Dumes Ripple, referring to the dilapidated riverfront where ships once unloaded and collected cargo. The company won a bid to reconsider the river frontage. Crescent Park opened in 2015 and is a 3.2-mile linear green space.

Bright became a jogging trail, dog park, old-growth foliage, and event space, all with unobstructed views of the Mississippi River.

One of the access points to the park is the huge bridge on Piety Street. “We used materials that naturally rust to symbolize the industrial history here,” Rivera says. “From the bridge you can see old wooden pillars in the water that once supported the quay sheds. We left them to preserve the past.”

Preserving history is something New Orleanians especially enjoy. Lucullus Antiques on Kentucky Street at the east end of the Bywater is a must-see.

It houses a shop, design studio and workshop, and is filled with treasures, from gilt mirrors to silver teapots, a collection of early 19th century copper cookware, and etched crystal decanters and glassware.

“Wherever I go, I love discovering the authentic charm of a place,” says proprietor Patrick Dunn. He and longtime colleagues Kelly Moody and Nathan Drews moved the store from the French Quarter to Bywater in 2020.

“Like the Bywater itself, our store is a destination. We’re not looking for tourists, we’re looking for intrepid travelers…people who are on an adventure in search of something special. With a passion for history and aesthetics, I love Bywater’s quirky, colorful small-village feel.”

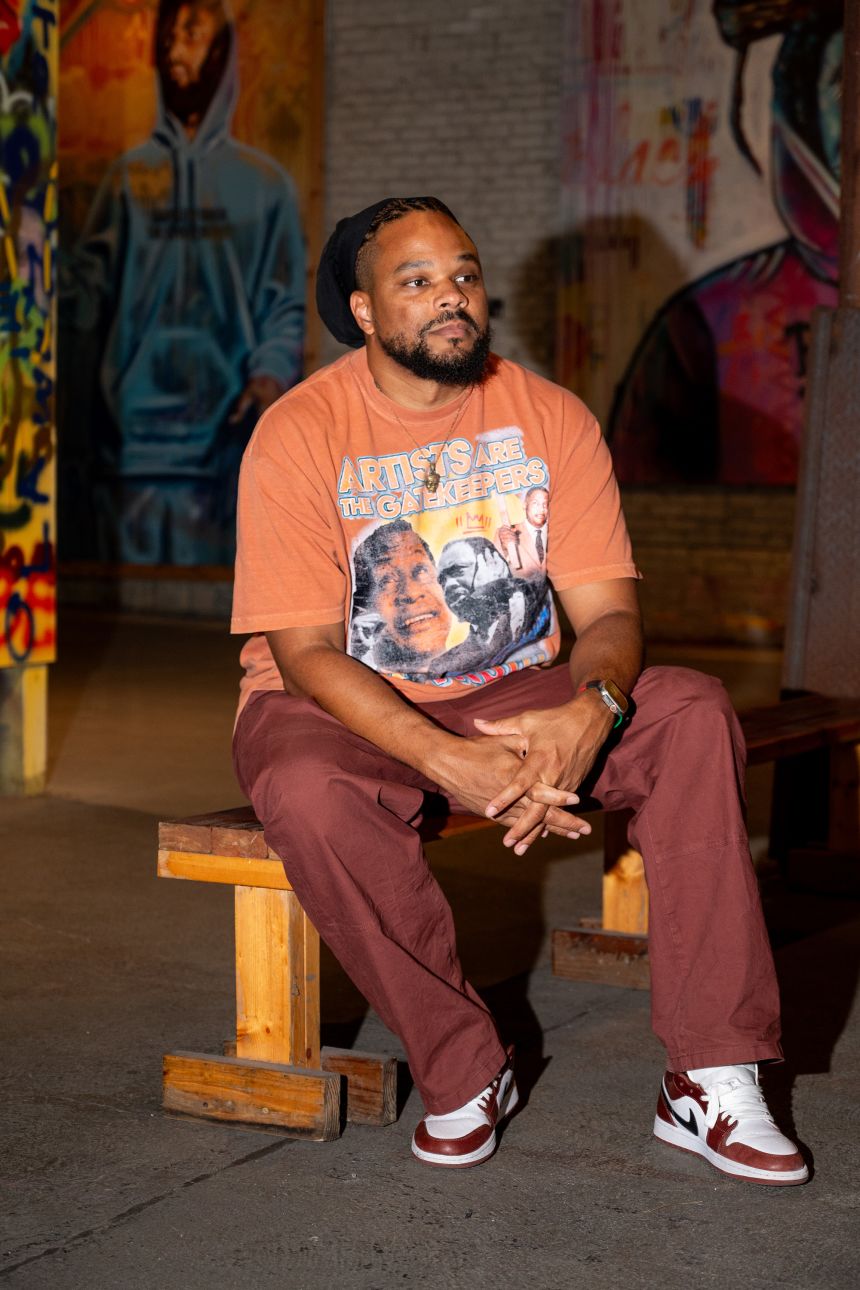

The village’s atmosphere comes from its embrace of all genres of art. On the west end, the city’s most prolific street artist, Brandan “BMike” Odums, opened StudioBE in 2016. The gallery’s towering murals highlight the Black experience and political struggle. It is also an education center for young artists, an event space, and a non-profit facility.

O’odhams’ two most famous murals are 30 feet tall and painted on the exterior walls of warehouses next to the railroad tracks on Homer Plessy Way, a corridor named after the famous Louisiana shoemaker and black activist.

“Black boys and girls are really the poster boys for this neighborhood,” Odums said. “We wanted to make sure the history here wasn’t erased. It was once a majority-black neighborhood, with generations of families living here. It’s always been an area of creative people. We want to keep Bywater sustainable as demographics change.”

As Patrick Dunn aptly stated, supporting independent businesses is essential to becoming travelers rather than tourists. It’s also easy and fun.

Tiger Rug Vintage in Saint-Claude sells fashion from the 1880s to the 1980s. Dauphin’s The Bargain Center is home to flea market venues and Mexican art galore. Euclid Records on Chartres Street has thousands of rare vinyl records, and Dr. Bob’s Folk Art Yard has indoor and outdoor sculptures that invite you to wander.

Bywater particularly supports entrepreneurs who think outside the box. In 2023, The Railyard Nola opened as a bed and breakfast specifically aimed at providing a safe and warm welcome for queer and trans travelers. The pool also offers day passes for non-guests.

Starting in 2024, costumes and wearable doll art will be available for purchase at the Monsters of the Underworld shop, and in 2025, the aforementioned Chance In Hell SnoBalls will open a permanent location on Dauphiné Street. Studio West is an adjacent boutique featuring eclectic fashion and retro home decor.

You can’t talk about creativity without mentioning the culinary arts. Because of this, the scene is both international and intensely experimental.

Acamaya is a sexy, red-lit temple to Mexico City cuisine, helmed by Chef Ana Castro. The restaurant, which opened in 2024, has been praised on multiple New York Times “Best of” lists for its deft execution of dishes such as chochoyote, a masa dumpling. Hers offers updated seasonal versions, including the current version with crab, pumpkin, mushroom, and peach rush pepper. Aguachile Verde from Sinaloa includes Gulf shrimp, cucumber, tomatillos, and serrano.

A dreamy European courtyard hidden behind a high privacy fence, N7 serves French cuisine with a Japanese twist. Marquee light bulbs hang from live oak trees, and camping lanterns dot the tables.

“(Our space) was an abandoned tire repair shop,” says Aaron Walker, who has owned and operated N7 with his wife, chef Yuki Yamaguchi, since 2015. Reservations are usually required for dining there, and the menu includes steak au poivre, steamed mussels, and pommes frites.

Advance reservations are required for the 10-course tasting experience at Saint-Germain, a block away. In the two-room cottage, you can pair scallops and guinea fowl with biodynamic wine.

Stop by Galaxy Tacos any time. The 1940s-era Texaco station sells soft barbacoa, homemade tortillas, smoky mezcal, and single estate tequila.

Ernie Foundas and Adrian Bell have been running the business near Generis, Switzerland for 13 years. The highly creative weekly menu includes homemade kombucha and kimchi, duck prosciutto, vegan Philadelphia cheesesteak, and more.

Across the road, Sneaky Pickle’s vegan/vegetarian offerings include cardamom cold brew, black rice egg rolls, and smoked tempeh Reubens. At night, the space transforms into Bar Brine, and meat dishes return to the menu, from rare tuna with yuzu to a killer 6-ounce cheeseburger.

Like art and architecture, long-established stores not only provide flavor but also foster deep connections with local communities.

Rather than a fancy dinner where you can meet locals, it’s breakfast or lunch at a storefront.

Bywater Bakery hosts live music sets outdoors on weekends and serves hot coffee and buttery pastries every morning.

Elizabeth’s combines bayou, roadside ambiance with high-calorie Cajun plates.

The joint smokes barbecue. The pulled pork plate is worth sitting down to eat, but it also has quirky perks. We sell single ribs that come off the bone to take home.

The best lunch in Louisiana? It’s takeout at Frady’s One Stop. Piety and Dauphine’s yellow corner storefront is decorated with folk art. Kirk Frady was educated at his father’s knee when the school opened in the summer of 1972.

“We want to preserve local lore,” Frady says. “Traditional red beans and rice, every Monday. Tuesday is meatloaf day…my grandmother’s recipe…and Friday is fried catfish.”

For more than 50 years, locals have been coming for po-boys, batteries, and beer. Organic parties are often held outdoors at noon. Once the seats at the steel tables and peeling front benches are filled, many people just sit on the curb.

“I’ve certainly seen the area change, but I never imagined it would become a tourist destination. Back when the area was rough and grandmas hid money in their bras, my dad ran a tab for families in need,” Kirk Frady says with a laugh. “My dad used to tell his customers, “If you make a wish for your first po-boy, it will come true.”

He handed me fried shrimp on French bread wrapped in wax paper. I ask Kirk for a wish.

“You can’t recreate an area like this,” he says. “So our wish is to protect it.”