LKAB facility in Kiruna, Sweden. The company announced on January 12 that it had discovered Europe’s largest known deposit of rare earth elements there.

Jonas Ekstromer | AFP | Getty Images

The ripple effects of Europe’s growing demand for raw materials are spreading all the way to Sweden’s far north.

Thousands of residents and buildings in Kiruna, a city located 145 kilometers (90 miles) north of the Arctic Circle, have been uprooted. This relocation project is considered one of the most radical urban transformations in the world.

Kiruna is being physically displaced due to land subsidence caused by the expansion of the vast metro ore mines. As part of a decades-long process, new housing is being built about 3 kilometers east of the old town and is expected to be completed by 2035.

“It’s a place that seems exotic to a lot of people, and in some ways it is, but it’s also a small town like a lot of other towns. It struggles with being too dependent on one company and faces challenges,” Jenny Sjöholm, a senior lecturer at Gothenburg University in Sweden, told CNBC in a video call.

Founded 125 years ago as a city for state-owned company LKAB’s iron ore mining operations, Kiruna is a small community that is both an important European space hub and home to the world’s largest underground ore mine.

All residents of Kiruna know that sooner or later they will have to leave their homeland because they are dependent on this mining industry.

Mats Terbenik

Chairman of Kiruna City Council

Although LKAB is small in global terms, it is a very important regional player, accounting for 80% of all iron ore mined in the European Union.

Alongside its iron ore operations, which are essential for the steelmaking process, LKAB recently identified one of the largest known rare earth deposits in Europe, further strengthening its position in mining materials essential to the green transition.

move around the city

There are several obstacles to a successful Kiruna relocation, with stakeholders from a variety of sectors raising political, economic, and environmental concerns. In fact, both the municipality and LKAB are seeking increased financial support from the state and the release of more land to accommodate the transformation.

Others have raised concerns about the relationship between resource extraction and the sustainability of local communities, particularly the potential impact on indigenous Sami reindeer herding and culture.

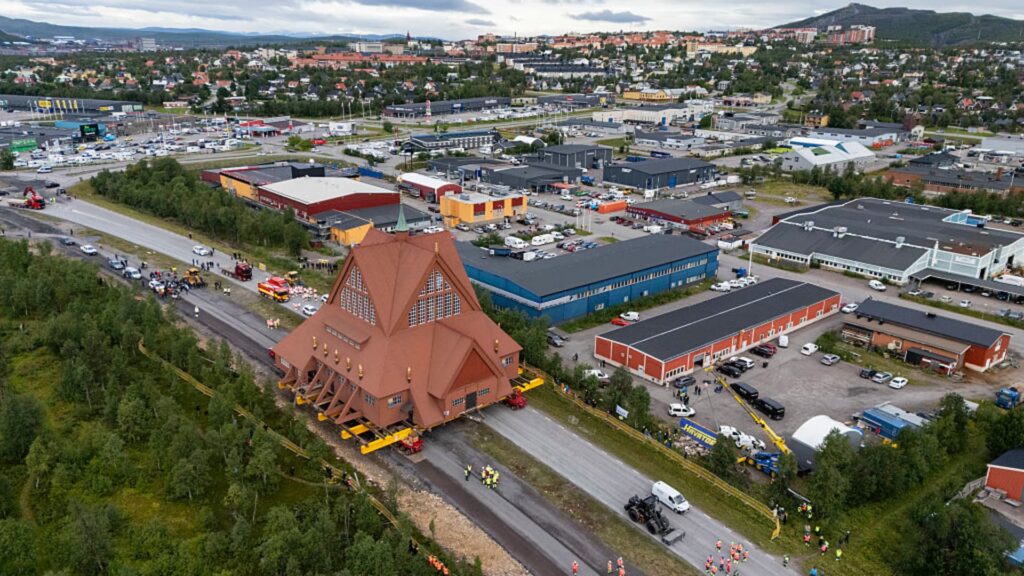

In this aerial photo, the Kiruna Church in Kiruna, Sweden, is transported by land to its new location on August 20, 2025. The church, which weighs 672,4 tons, is being moved in its entirety to a new location 3 kilometers away to avoid damage from LKAB’s iron ore mine.

Bernd Lothar | Getty Images News | Getty Images

First planned in 2004, the city’s relocation attracted international attention in August 2025 during the grand relocation of the iconic Kiruna Church. In a feat of engineering, the entire 113-year-old wooden building was moved in a special trailer over two days.

However, around the same time, LKAB announced that the expansion of its iron ore mine would require the relocation of an additional 6,000 people and 2,700 homes. The mining company responsible for the move estimates compensation costs of SEK 22.5 billion ($2.4 billion) over the next 10 years.

Niklas Johansson, LKAB’s senior vice president for communications and external relations, told CNBC that those asked to relocate are being offered an additional 25 percent above the market value of their property, or the construction of a new home. About 90% of people chose to live in new homes, Johansson said.

“The problem at the moment is that there is very little land that is owned by local governments (or) that can be made buildable from an administrative standpoint,” Johansson said.

“They had to buy land from countries that own most of the land above the Arctic Circle. And here you have conflicts with reindeer herding, conflicts with defense, conflicts with nature, etc.,” he added.

“We live by eating minerals”

Mats Tervenik, chairman of the Kiruna City Council, described the city’s relocation as a “huge project” that could create huge opportunities for European citizens for decades to come.

He added that success will partly depend on greater financial and political support from both the Swedish government and the European Union.

“There is a situation that can be called a big fight between the local government and the LKAB, between the local government and our government,” Terbenik told CNBC in a video call.

“The EU must come forward to support us. It is not enough to determine that we have important and strategic minerals. Of course, the EU must support us with political statements and funds,” he added.

CNBC contacted spokespeople for the Swedish government and the European Commission, the EU’s executive agency.

A foundry worker handles molten metal at the Bessaid plant, which primarily serves the automotive industry, in Elorio on May 26, 2025.

Ander Gilenaire | AFP | Getty Images

The EU recognizes LKAB’s new rare earth deposits as being of strategic importance under the Critical Materials Act, which aims to meet 40% of the region’s annual demand with domestic production by 2030.

When asked about the reaction of Kiruna residents to the relocation effort, Terbenik said, “Some residents are sad because they will lose a lot of memories. This is sad because they have grown up in this house for two or three generations.”

“But on the other hand, as everyone knows, we live off minerals,” he says. “Kiruna is built on minerals, so all the residents of Kiruna know that sooner or later they will have to leave their homeland because they are dependent on this mining industry.”

In the cold?

One aspect that is causing concern for people on the move is that the new city of Kiruna can be up to 10 degrees colder in winter.

Research from the University of Gothenburg found that Kiruna’s new city center is laid out in a grid of areas where cold air gathers, with tall buildings and narrow roads, making it likely that the sun is low enough to reach the ground in many months of the year.

Workers photographed in an underground tunnel at the LKAB iron ore mine in Kiruna, northern Sweden, on August 21, 2025.

Jonathan Knackstrand | AFP | Getty Images

“Kiruna is a winter city. It’s a cold Arctic city. We have long winters and long snow seasons. It’s rarely -35 degrees, but it can get this cold for certain periods in the middle of winter, and there’s a huge difference between -15 degrees and -25 degrees, which is not uncommon,” Sjoholm said. Sjoholm, an architectural heritage expert, has been following urban relocation efforts for 25 years.

“We’re already in the middle of a long winter season, and the colder it is, the less human comfort, but the more vulnerable things become, so to speak,” she added.