“Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void, but out of chaos.” Mary Shelley, “Frankenstein,” 1818.

“War is chaos. It always has been. But technology makes it worse. It changes the fear.” Pierce Brown, “Golden Son,” 2015.

Drones – and artificial intelligence – have reshaped the modern battlefield and are about to do so again.

Nowhere is that more evident than in Ukraine.

Invaded by Russia in 2022, outmanned and outgunned by one of the world’s strongest militaries, Kyiv quickly proved that drones – in the air, on the ground, and at sea – could hold off a Russian victory that many expected within weeks, if not days.

Cheaper and easier to build than manned vehicles, and in some cases more effective, drones are a military planner’s dream – and greatly reduce the risk of a pilot or operator being killed in action.

Much like the Kalashnikov rifle in the previous century, mass adoption of drones became an asymmetric weapon of choice for forces facing long odds in global warfare, such as the Hamas militant group in Gaza; anti-junta rebels in Myanmar’s civil war; and the militaries of poorer nations, including many in Africa.

But the Goliaths have caught up, while – according to one report – drug cartels the world over are innovating, improving and adapting drones to fight the narco-wars of the future.

“It’s like gunpowder. That’s how insanely it’s changed the war,” Patrick Shepherd, a former US Army officer, said of the advent of cheap aerial drones.

It’s invention from chaos, as myriad regional conflagrations coincide with an era of unparalleled technological advance.

It’s probably just the beginning.

Drones aren’t a recent invention. Britain and the United States experimented with radio-controlled unmanned aircraft during World War I, according to the Imperial War Museum in London.

The term is thought to have come from one of the remote-controlled aircraft Britain was developing between the First and Second World Wars, the De Havilland DH82B Queen Bee, which first flew in 1935.

“We were flying hundreds of drones over North Vietnam during the war,” said Russ Lee, a curator in the aeronautics department at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington. During that Southeast Asian conflict in 1960s and early ‘70s, US forces began using drones for many of the same missions we see today – reconnaissance or carrying munitions, or for use as decoys and psy-ops platforms, according to the Imperial War Museum.

The US began widespread use of drones during Operation Desert Storm, the response to Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. The Tomahawk land-attack missile – a cruise missile but also an unmanned aerial vehicle as it can change course and target in-flight – saw its first combat in 1991.

The same year, a group of Iraqi soldiers on a Persian Gulf island surrendered to a US Navy reconnaissance drone, according to the Air and Space Museum.

During America’s “war on terror,” larger drones like the Predator and Reaper became key assets, stealthily striking targets, hunting down militant leaders and offering protective cover to US ground troops.

But drones came to the forefront of warfare relatively recently, some analysts say, with the 2020 conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh a major turning point.

Back then, Azerbaijani forces repurposed agricultural biplanes into decoy drones. Then when Armenian air defenses revealed themselves to take out the decoys, air combat drones (UCAVs) and artillery eliminated the Armenian anti-aircraft sites, eventually giving Baku control of the skies.

“The use of UCAVs after the 2020 conflict point to a new established trend amongst UCAV users, especially nations which do not have large resources to invest in military technology,” UK Royal Air Force Flight Lieutenant Chris Whelan wrote in a 2023 paper on the conflict.

Fighting has raged at the edge of Eastern Europe for well over three years now, and Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s forces are still far from being able to declare victory.

Kyiv’s drones deserve much of the credit.

They’ve blasted Russian tanks to burning hulks, sunk ships from Moscow’s Black Sea Fleet, and emerged from clandestinely placed containers to destroy Russian strategic bombers on the ground. They’ve hunted down individual Russian soldiers in fields, in trenches and inside buildings by flying through open windows.

They’ve even become the last-gasp hope of troops on their own side, as was the case for a wounded Ukrainian soldier who was able to cycle away from the front after a drone air-dropped him an electric bike.

While in the early stages of the war both sides relied heavily on existing foreign-made drones, they’ve built their own drone technology and assembly lines.

For instance, Russia is now making the Shahed attack drones it once bought from Iran in the thousands.

Bayraktar drones bought from Turkey helped Ukraine repel Russian advances early in the war. Now, according to the British Defense Ministry, which signed a landmark drone development deal with Kyiv earlier this year, “Ukraine is the world leader in drone design and execution.”

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has become, in a sense, the world’s best drone salesman, traveling to NATO member capitals to pitch them up-to-date, fast-evolving drone technology in exchange for help in the war.

Even US President Donald Trump has taken note.

“They make a very good drone,” he said recently of Ukraine.

Kyiv would probably have lost the war by now, had it not been able to adapt widely available commercial tech to build its drone forces and incorporate it into its military strategy, said Kateryna Bondar, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

“It’s 100 percent accurate to say this. And we can see this especially by the numbers,” Bondar said in an online CSIS presentation in May.

Ukraine built as many as 2 million drones last year, up from 800,000 in 2023, according to Bondar. Next year it will build 5 million, she estimates.

Shepherd, the former US Army officer, who served in Iraq in 2005-06, told CNN that cheap aerial drones could have changed that conflict and put the US at a huge disadvantage.

“If we had faced these in Iraq, it would have been terrible for us,” said Shepherd, now chief sales officer for Estonian drone manufacturer Milrem Robotics, who has made numerous trips to Ukraine.

Inside the US military’s push for small, cheap drones that have transformed the battlefield

Warfare has been fertile ground for invention since before the time of Alexander the Great, with minds focused – and production cycles accelerated – by the existential stakes.

It’s been no different in Ukraine, where innovation is constant.

Bondar notes how Ukraine, when Russia was able to jam the signals to earlier radio-operated models, developed drones controlled by fiber-optic cable. While physically tethered to their controller like a kite, the fiber-optic drones can operate at distances as large as 30 miles (50 kilometers), she said.

The changes don’t require months of development work in labs or factories, according to analysts. Drones are going through “quick iteration cycles at the front,” Samuel Bendett, one of the authors of the CSIS report, told CNN.

Workshops aren’t far from the front lines and in some cases are mobile, so commanders and drone controllers can give first-person feedback to developers and technicians. Sometimes, only small tweaks are needed to change a drone’s performance.

“This often concerns changing frequencies, modifying cameras and sensors and changing flight patterns and other characteristics,” Bendett said.

In announcing its drone deal with Kyiv in June, the UK Defense Ministry said drone technology is evolving, on average, every six weeks.

Shepherd told CNN he’s seen drones go from paper sketches to deployment on the Ukrainian battlefield in a month.

Russia has suffered devastating losses in its invasion – more than a million casualties, according to Western estimates.

So Moscow, naturally, has fought back with a massive drone-building program of its own. CSIS analysts say Moscow now produces 4 million drones a year, and that number is projected to increase.

Russia’s fiber-optic, jamming-resistant drones are the equal to Ukraine’s, and Russia is believed to be producing them in larger numbers.

Its top-secret drone unit, the Rubicon Center for Advanced Unmanned Technologies, has been seen by many as a game-changer on the front lines.

“Rubicon formations remain a leading problem for (Ukrainian) drone operators, not only the drone companies themselves, but because they train other Russian drone units,” notes Michael Kofman, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment.

The secretive factory fueling Moscow’s drone war in Ukraine

While most of the drones used in the war are unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, Ukraine has also built highly effective sea drones (USVs) and land drones.

Kyiv’s sea drones have sunk Russian warships and shot down Russian military aircraft with surface-to-air missiles. Recently, Ukraine launched smaller bomber drones from a USV, essentially a small drone aircraft carrier, that blasted Russian radars in Crimea, according to the Ukrainian military.

Ukraine’s USVs have done what few would have thought possible when the war began in 2022, analysts say – negating Russia’s once-overwhelming advantage in the Black Sea.

As in Ukraine, cost-effective unmanned vehicles can transform battlefields and bring deadly firepower to militaries that were previously outgunned, whether for budget constraints or lack of access to tech.

The countries of Africa are prime examples.

In an April paper for the US Defense Department’s Africa Center, associate professor Nate Allen says 36 of the continent’s 54 nations have acquired drones in the past two decades, with acquisitions spiking sharply since 2020.

While the African drone market is largely import-driven – Turkey and China being the main sources – nine African countries are now producing indigenous drones, Allen wrote.

And it’s not just African governments boosting their drone fleets; non-state actors in nine countries on the continent have employed armed military drones, according to Allen.

Among them was the Libyan National Army, which battled the UN-backed Government of National Accord during Libya’s 2014-20 war. That conflict, which left the country “mired in instability and political fragmentation,” was the “world’s preeminent drone theater” at the time, Allen said.

Last July in Sudan, the leader of the country’s armed forces survived a drone attack, allegedly by the rebel Rapid Support Forces, during a military academy graduation ceremony, Allen noted.

Non-state actors in Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria and Somalia are also employing drones, Allen said.

“Unmanned systems are … reshaping the battlespace in most African conflicts,” he said.

In Asia, Myanmar’s anti-junta rebels in 2023 were essentially able to use commercially purchased drones to replace artillery, “bombarding” the military regime’s forward operating bases in the mountainous regions along its borders for “days on end,” said Morgan Michaels, research fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) in Singapore.

The rebels’ drone assaults resulted in the military pulling back and ceding control of much of its border territory to the insurgents, Michaels said.

“There’s been a major shift in the balance of power in Myanmar over the past two years and in large part this is due to the ability of opposition forces to incorporate UAVs in their fighting doctrine,” Michaels said.

Meanwhile in the Middle East, Hamas militants in Gaza used drones to knock out Israeli observation posts prior to their deadly October 7, 2023, raid into southern Israel, an action that precipitated a war that has killed more than 60,000 Palestinians.

As their built-in smarts advance in leaps and bounds, the weapons could soon outgrow their name – “drone,” denoting an automaton unthinkingly executing a given task.

Artificial intelligence now gives some the on-board ability to identify targets, look for their weak points and execute an attack, all with split-second timing.

Near the bleeding edge of these advances is Auterion, an international defense software company whose tech turns existing drones into “autonomous weapons systems.”

The company recently signed a $50 million deal with the US Defense Department to supply 33,000 AI-driven drone “strike kits” to Ukraine.

Company founder and CEO Lorenz Meier told CNN that humans guide the drones to the area of the target, maybe about a kilometer away, then take off the reins. The drones then track and maneuver to go in for a strike, while resisting enemy jamming.

Does that augur a dystopian battlefield where robots make kill decisions on their own? Meier stressed such fears were overblown.

On the battlefield of the future, he says, he expects drones to be a better form of artillery, just as deadly but at a fraction of the cost.

Artillery is an area weapon, he said. Shells are fired around a grid, with the expectation that enemy troops and equipment are somewhere in that grid.

Meier said his Ukrainian partners have told him that using drones for reconnaissance and spotting for current artillery fire has enabled them to cut the ammunition needed to kill a specific target from 60 shells to six.

But armed drones know exactly where each soldier, truck or tank is and can directly attack them, making them even more efficient – “times six,” says Meier. So those 33,000 drones with Auterion software bring the offensive capacity of 198,000 artillery shells.

And it’s cost-effective, Meier says, noting that a single artillery shell costs $2,000 to $4,000. Individual drones can cost $1,500 or less.

In an August report from Defense One, US Navy Rear Adm. Michael Mattis said an effort is underway to show how much money naval drones (USVS) can save over destroyers (DDG) that are now the backbone of the US Navy’s surface fleet.

“We think that with 20 USVs of different, heterogeneous types, we could deconstruct a mission that a DDG could do. And we think we could do it at a cost point of essentially 1/30 of what a DDG would cost,” Mattis wrote.

But Meier said that, at least on land, artillery will still have its place, especially against an entrenched defender with strong fortifications.

The drones that have been getting the most attention in Ukraine, and other current conflicts like Gaza or Myanmar, are medium-sized models, from something you can hold in your hands to about the size of a small pleasure boat in the case of Ukraine’s seaborne drones.

But the drone spectrum is expanding, spanning some the size of insects and others the size of ocean-going ships.

Earlier this year, Chinese state-run news outlet CCTV posted a video of military academy students looking at mosquito-sized drones, machines not much bigger than a person’s fingertip.

Developed by the National University of Defense Technology, the drone can be used for surveillance and reconnaissance.

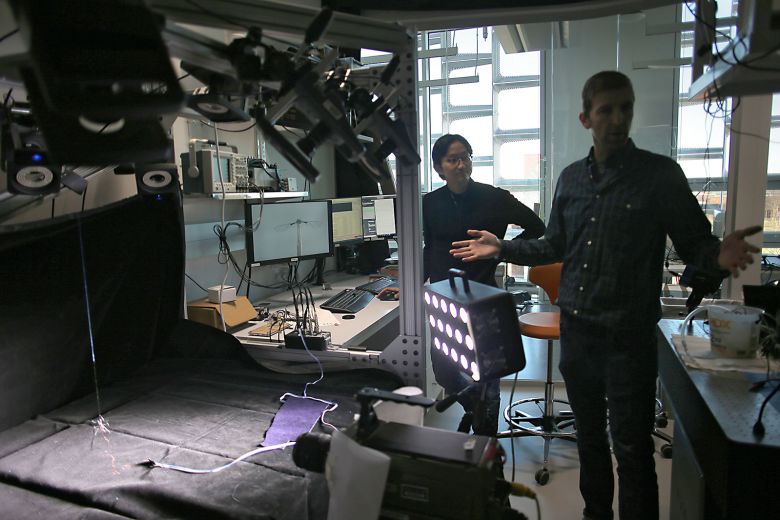

But US and Norwegian researchers may be a few years ahead of their Chinese counterparts in developing so-called nano-drones.

Six years ago, developers at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute unveiled the RoboBee, which could have commercial and military uses, including reconnaissance, according to the institute’s website.

“A RoboBee measures about half the size of a paper clip, weighs less than one-tenth of a gram, and flies using ‘artificial muscles’ comprised of materials that contract when a voltage is applied,” the website says.

The Black Hornet, from Norway’s Teledyne FLIR Defense, is a bit bigger than the RoboBee. About the size of a pigeon and with a single rotor, it looks like a toy helicopter.

It can be launched in 20 seconds by a single soldier and provide battlefield reconnaissance at a distance of three kilometers, Teledyne says.

It’s already in the arsenals of 45 militaries and security forces worldwide, according to the company.

The next big step may be bio-robotics, according to SWARM Biotactics, a German company designing “living, intelligent” systems, specifically swarms of cyborg “cockroaches equipped with a custom-built backpack for control, sensing, and secure communication.”

At the larger end of the spectrum, the US government’s Defense Advanced Research Products Agency (DARPA) in August christened what it calls the USX-1 Defiant, an autonomous, unmanned surface vessel.

DARPA says the 180-foot, 240-ton ship is “designed from the ground up to never have a human aboard.”

In a press release, DARPA mentions a key attribute of the smaller drones like those used in Ukraine: rapid production.

With no need to accommodate and ensure human survivability, the Defiant class can be produced more quickly and at a larger scale than crewed vessels, “which will create future naval lethality, sensing and logistics,” DARPA director Stephen Winchell said in a press release.

Drones will have a military role below the surface too.

China showed off its newest ones in its September 3 military parade.

The PLA Navy drones, known as extra-large uncrewed undersea vehicles (XLUUVs), are shaped like torpedoes, but are huge – around 65 feet long, according to an analysis by submarine expert H I Sutton.

Their exact role isn’t yet known, but Sutton says they are among five XLUUVs in China’s undersea drone fleet, which he says is the world’s largest.

One of the biggest and newest undersea drones in Western militaries is the Ghost Shark, an extra-large autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) developed by the Australian military and defense tech newcomer Anduril.

While specs haven’t been released, for security reasons, the Ghost Shark looks to be the size of a large shipping container and its modular construction will allow it to be customized for a range of undersea missions.

When it was introduced last year, Chris Brose, Anduril’s chief strategy officer, said the company and Australia are in the “process of proving” that “these kinds of capabilities can be built much faster, much cheaper, much more intelligently.”

The Australian government in September signed a $1.1 billion deal with Anduril for a fleet of Ghost Sharks, with Anduril calling it “the start of a new era of seapower through maritime autonomy.”

And it’s not just big countries that see drones as a key pillar of future defenses.

Singapore in October launched its first drone “mothership,” officially called the Multi-role Combat Vessel.

Displacing about 8,500 tons, it’s about the size of large frigate or small destroyer and will act as a platform for “unmanned aerial, surface and underwater systems for the conduct of naval operations,” the country’s Defense Ministry says.

More akin to a Silicon Valley start-up than to Boeing or Lockheed Martin, Anduril and Auterion are among a new breed of defense contractor drastically changing the industry.

Based in Costa Mesa, California, Anduril envisions itself as controlling the entire development of a weapons system, including the hardware and the technology specifically made to power it.

Palmer Luckey, who started Anduril Industries after selling the Oculus VR to Facebook in 2014, says he’s building defense systems in a different way, not waiting for the government to tell him what it wants, but by selling Anduril-designed systems that would fit a government need.

Luckey says that enables him to find the most efficient manufacturing processes and cost-effective sources, bring costs down for taxpayers, as well as shortening development time.

To make it all come together in the United States, Anduril is building a huge $1 billion factory near Columbus, Ohio, called Arsenal-1.

“Arsenal-1 will redefine the scale and speed that autonomous systems and weapons can be produced for the United States and its allies and partners,” the company’s website says.

Auterion, based in Arlington, Virginia, with facilities in Germany and Switzerland, pushes a different model.

It says it can put its software in drones already on the market and turn them into killer swarms and other systems.

Meier, Auterion’s founder, sees his company as a sort of Microsoft to Anduril’s Apple. The latter controls the software, the operating systems and the hardware. The former makes software that can work across the hardware of others.

These companies are injecting new speed and urgency into arms development, which has traditionally relied on a few large companies with huge contracts, that guaranteed big profits even if what they produced didn’t always live up to what was promised.

And they aren’t the only new names in the modern arms industry. US firm Kratos is developing unmanned aircraft for the US and Taiwan militaries.

General Atomics is competing with Anduril for the US’s “loyal wingman” drones, which can fly alongside US fighter aircraft.

Earlier this month, General Atomics said it successfully paired an MQ-20 Avenger unmanned jet with a F-22 stealth fighter in a test with the F-22 controlling the drone in flight.

Shield AI turned heads in late October when it revealed plans for the X-Bat, a drone that can fly autonomously or as a loyal wingman, calling it a “revolution in airpower.” It’s a vertical takeoff and landing aircraft with a range of more than 2,000 miles that could turn just about any ship with a flat surface into an aircraft carrier.

And there are more familiar – if surprising – names entering the drone business.

At a recent defense expo outside Seoul, the defense arm of Korean Air – yes, South Korea’s largest passenger airline – showed off a line of drones, everything from human-sized loitering munitions to a loyal wingman of its own.

The influence of these new defense contractors is reflected in this year’s list of the world’s top 100 defense companies, based on revenues, compiled by the website Defense News.

Anduril entered that list for the first time, Defense News says, joining Kratos and Palantir Technologies, which produces AI-driven data analysis software.

While Anduril, Auterion, and SWARM Biotech are among the leaders in Western drone innovation, China makes a strong case for being the leader in the field.

“China dominates the cheap commercial drone industry, which puts it in a good position” to do the same on the military side, William Freer, a research fellow at the Council on Geostrategy in the UK, told CNN.

“They are experimenting with long-range underwater drones, long-range UCAVs, and a new ‘drone carrier’ seems to be under development for their navy,” he said.

But where China may be gaining the upper hand is in drone defenses, analysts say, after Beijing noted the success of low-priced drones against traditionally high-priced air defenses in the Ukraine war.

Compounding that evidence, during exercises last year, traditional Chinese drone defenses were only able to knock out around 40% of incoming aerial targets, analysts Tye Graham and Peter Singer noted in a recent report on the military website Defense One.

The result has been massive investment in counter-drone systems in China.

“The (Chinese) market now features more than 3,000 manufacturers producing anti-drone equipment in some form,” Graham and Singer said.

“Recent procurement data reveal a dramatic rise in the acquisition of counter-UAV systems,” they said, with the number of procurement notices more than doubling for such systems from 2022 to 2024.

Some of those systems are mind-boggling. One is a high-powered microwave weapon showcased at Airshow China last year.

“Described as the equivalent of ‘launching thousands of microwave ovens into the sky,’ the system delivers rapid, area-wide electromagnetic pulses capable of frying drone electronics within a 3,000-meter radius,” they said.

Meanwhile the world’s preeminent military – the US – isn’t keeping up, according to a June report from the Heritage Foundation think tank.

“Adversary development of drone technology is currently outpacing that of the US, as well as US drone countermeasures,” the report said.

“While the US has taken important initial steps to develop advanced counter-drone systems and training programs, these steps remain fragmented, underfunded, and unevenly implemented,” it said.

And that’s just in the counter-drone realm. Two recent news reports, from Reuters and The New York Times, pointed out how the US trails China in developing sea and air drones, respectively.

No less than the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, retired Gen. Mark Milley, paints a dire picture for the US.

Future wars “will be dominated by increasingly autonomous weapons systems and powerful algorithms,” Milley, along with analyst and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, wrote in an opinion piece for Foreign Affairs last year.

“This is a future for which the United States remains unprepared,” they wrote.

To its credit, the Trump administration in June published an executive order, titled “Unleashing American Drone Dominance,” with one of its 10 sections pushing government efforts on “Delivering Drones to Our Warfighters.”

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth followed that up with a July memo vowing to cut through red tape to get the latest drone technology into the hands of US troops and train them how to use it.

But ramping up US drone production to Chinese levels could take years. And, as Hegseth’s memo noted, “US units are not outfitted with the lethal small drones the modern battlefield requires.”

US Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll subsequently told the Reuters news agency that the service aims to buy at least a million drones in the next two to three years – up from about 50,000 annually today.

Instead of partnering with larger defense companies, he said the Army wanted to work with companies producing drones that could have commercial applications as well.

“We want to partner with other drone manufacturers who are using them for Amazon deliveries and all the different use cases,” he said.

But some are urging restraint, saying drones and AI are not the end-all on future battlefields.

“Far more important for an Indo-Pacific conflict is (China’s) build-up of their long-range missiles and ‘legacy’ platforms such as frigates, destroyers, submarines, and long-range fighter aircraft (such as the J-20) which are expanding at an alarming rate,” said Freer at the UK’s Council on Geostrategy.

At a CSIS event in August, Britain’s outgoing defense chief of staff, Adm. Sir Tony Radakin, cautioned Western defense leaders about becoming too enamored of drones and AI – just because of they’re new and cool.

“I worry that we almost become drone-tastic,” the British admiral said.

“My worry … is that we embrace our inner geek by focusing on the technology and its applications, and we miss the broader point about the strategy that needs to accompany it,” Radakin said.

The machines themselves aren’t going to win conflicts, according to Radakin. Users must be adjusting tactics and defense plans at pace with the rapidly evolving technology.

And drones can’t occupy territory, at least not yet. They aren’t boots on the ground.

“We’re still going to need submarines, and jets, and armored vehicles alongside our mass ranks of drones and uncrewed systems,” Radakin said.

“You’re still going to need to hold ground. That’s the physical relationship with a nation’s territory,” he said.

Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb, the much-ballyhooed operation in which drones smuggled into Russia in containers destroyed a large number of Russia’s strategic bombers, illustrates Radakin’s point.

The attack was “spectacular” but did nothing to change the situation on the ground, Amos Fox, a professor in the Future Security Initiative at Arizona State University wrote in an August article in the Small Wars Journal.

“This type of operation potentially illuminates innovative ways that drone warfare can be used in future war, but it also emphasizes a disconnected understanding of how operations support strategy. The operation did not affect the strategic or operational balance of power as it relates to control of Ukraine’s land, which is a key victory condition for both Russia and Ukraine,” Fox wrote.

Drones fight what Fox calls “micro-engagements” – small, contained actions, often one drone vs. one target.

Such actions don’t create the strategic pressure on politicians to end wars like losing or gaining territory does, he argues.

While drones can’t control land or be an occupying army, they can give the underdog the ability to prolong the battle or create a stalemate.

The current wars in Ukraine and Myanmar are prime examples. Quick victories that many observers expected from the big guys – Russia and the Myanmar military – quickly evaporated as the little guys – Ukraine and the Myanmar rebels – used drones to level the playing field. Those wars have now lasted 3.5 and 5 years respectively.

“Technological innovation, particularly in drone warfare and artificial intelligence, is making conflict more accessible and more asymmetric – but with that, also more difficult to resolve,” according to a June analysis from the Vision of Humanity, part of the global Institute for Economics and Peace.

It’s creating what the group calls “forever wars,” conflicts that “defy resolution and sap resources for years, if not decades.”

The group’s Global Peace Index shows 59 state-based conflicts now ongoing, the highest number since World War II, with 78 countries involved.

And technology like drones prevents clear-cut victories, it says, with the share of conflicts ending in decisive victories at just 9% in the 2010s, compared with 49% in the 1970s.

“Similarly, those resolved through peace agreements have declined from 23% to only 4%,” it says.

Technology is prolonging the chaos, making it worse.