With electricity prices soaring, voter anger growing and the US midterm elections just around the corner, the artificial intelligence industry’s data centers are increasingly under fire.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, residential utility costs rose by an average of 6% nationwide in August compared to the same period last year.

The reasons for price increases are often complex and vary by region. But in at least three states with high concentrations of data centers, electricity prices rose much faster than the national average over the same period. For example, prices rose 13% in Virginia, 16% in Illinois, and 12% in Ohio.

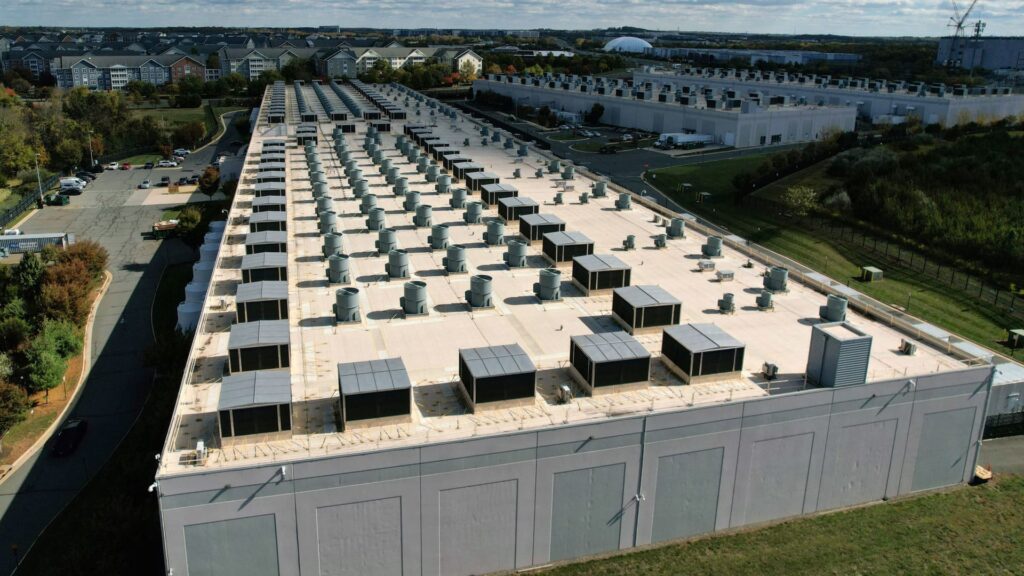

Tech companies and AI labs are building data centers that consume more than a gigawatt of electricity in some cases. This equates to more than 800,000 households, which is essentially the size of a city.

Virginia has the highest concentration of data centers in the world. Democrat Abigail Spanberger won a landslide victory in the recent gubernatorial election by running a cost-of-living campaign. Spanberger placed at least some of the blame for soaring electricity prices on data centers and promised to make tech companies “own their fair share” of rising costs.

The gubernatorial race could portend political headwinds for the AI industry’s data center expansion, with midterm elections a year away and affordability a central issue for Democrats. In Washington, some Democratic senators are targeting President Donald Trump’s close relationships with leaders of big tech companies and AI labs.

Sens. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut and Bernie Sanders of Vermont this week took aim at what they called the White House’s “sweetheart deals with big tech companies” and accused the administration of failing to protect consumers from being “forced to subsidize data center costs.”

“The technology clash is real,” said Abraham Silverman, who served as general counsel for the New Jersey Public Utilities Commission from 2019 to 2023 under outgoing Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy.

“Data centers are not always great neighbors,” said Silverman, now a researcher at Johns Hopkins University. “They tend to be noisy and can be dirty. There are a lot of communities that don’t want more data centers, especially in places where they’re very densely packed.”

Virginia, Ohio, Illinois

Looking at the top five states for data centers can help sort out some of the politics surrounding data centers from what’s actually happening to power rates.

Virginia, Illinois and Ohio are among them, and most are served by the same transmission operator, PJM Interconnection. PJM is the nation’s largest power grid, serving more than 65 million people in 13 states, including New Jersey, where Mr. Silverman advised the State Electricity Commission.

The PJM power grid faces a significant imbalance between supply and demand. To ensure the reliability of the power grid, auctions are held to secure power capacity from power plants. The auction for 2024-2025 was worth $2.2 billion. Since then, the bill has increased by more than 500% to $14.7 billion from 2025 to 2026.

The independent watchdog that monitors these PJM auctions found that data center demand, combined actual and forecast, accounted for $9.3 billion, or 63% of the total power capacity bill in 2025-2026. In the latest auction, the price rose another 10% to $16.1 billion.

“Increased data center loads are the primary driver of recent and anticipated capacity market conditions, including increased total forecast loads, tight supply-demand balances, and high prices,” Monitoring Analytics said in its June Independent Market Monitor report.

Those capacity prices will be reflected on consumers’ utility bills, Silverman said. PJM’s data center load is also impacting prices in states where it is not an industry leader, such as New Jersey, where prices have increased about 20% year over year. Democrat Mikie Sherrill won the Garden State’s gubernatorial election on a promise to freeze electricity rate increases.

“This is a very big component of the affordability crisis that we’re experiencing right now,” Silverman said of data centers’ impact on capacity pricing.

Silverman said there are other reasons for rising electricity prices. He said the aging power grid needs to be updated amid widespread inflation and the cost of building new lines is rising by double digits.

Utilities also point to increased demand from widespread electrification of the economy, including the expansion of domestic manufacturing and the adoption of electric vehicles and electric heat pumps in some regions.

Although some Democrats are blaming the White House, the conditions leading to higher power prices in the PJM area began before the second Trump administration took office.

Silverman said PJM’s process for bringing new power online “crashed and burned.” Tax subsidies under the Inflation Control Act have led to a surge in renewable energy projects waiting to connect to the grid. PJM has struggled to maintain approvals, which can take up to five years in some cases.

PJM’s watchdog said that without the data centers, grid power supplies could have been tighter, but demand growth would have slowed and the market would have been given more time to deal with it.

“It is misleading to claim that capacity market results are simply a reflection of supply and demand,” the watchdog group said, calling the rapid increase in load from data centers “unprecedented.”

President Trump has promised to cut electricity rates in half in his first year in office. That hasn’t happened yet, and it’s unlikely to happen in the next few years because supply and demand are tight.

“It’s hard to imagine that utility costs will go down in the next 10 years,” said Rob Gramlich, president of Grid Strategies, a power sector consulting firm.

Texas and California

However, in other states, the relationship between rising electricity prices and data centers is less clear. For example, Texas has more than 400 data centers, second only to Virginia. However, prices in the Lone Star State rose about 4% year over year in August, below the national average.

Texas operates its own power grid, ERCOT, and is a relatively quick process that allows new electricity supply to be connected to the grid in about three years, according to a February 2024 report from Brattle Group.

Meanwhile, California has the third-highest number of data centers in the nation and the second-highest residential electricity rates, nearly 80% above the national average. However, prices in the Golden State increased by approximately 1% year-on-year in August 2024, far below the national average rate of increase.

One of the reasons California’s electricity rates are so much higher than in most areas of the country is the costs associated with wildfire prevention. PG&E, the state’s largest utility, said in March that it expected rates to be stable this year as costs related to wildfire prevention are deducted from customers’ bills.