This week the world passed a nuclear milestone. And, perhaps surprisingly, given the recent series of saber rattles from Russia, the United States, and elsewhere, this is a positive thing.

“As of today, the world has gone 8 years, 4 months, and 11 days without a nuclear test…Every day without a nuclear explosion from now on will be a new record,” Dylan Spalding, senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), noted the milestone in a blog post on Wednesday.

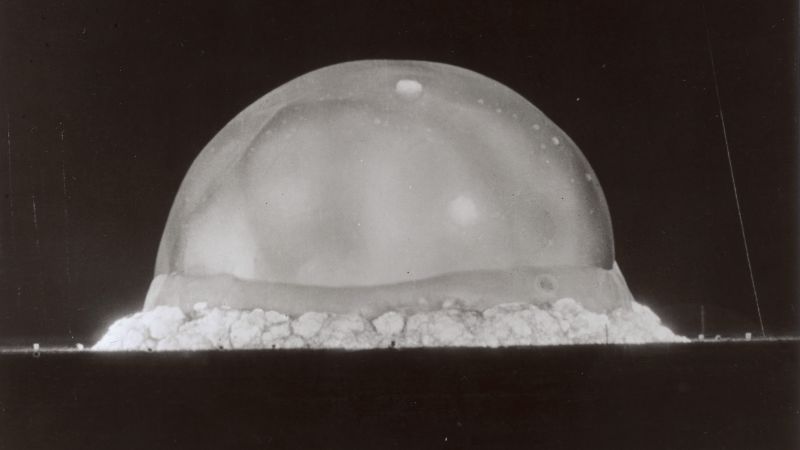

Wednesday’s watershed marks the longest period on Earth without a nuclear explosion since the dawn of the nuclear age on July 16, 1945, when the United States detonated a nuclear test device at Alamogordo, New Mexico, near the end of World War II, leading up to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.

North Korea conducted the world’s last nuclear test on September 3, 2017.

The longest period without a test was from May 30, 1998, when Pakistan conducted its last test, to October 3, 2006, when North Korea conducted its first test.

Spaulding warned of how fragile this “winning streak” has become in light of US President Donald Trump’s threat to resume nuclear testing.

“Re-opening this Pandora’s box is unnecessary and unwise,” Spaulding wrote.

“Unrestricted testing creates competition, instability, and an almost intolerable degree of uncertainty on top of existing global instability,” he wrote.

In another red flag, President Trump said he was willing to let the U.S.-Russia agreement, which limits the number of nuclear weapons each side can deploy, expire on February 5.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Russia has the world’s largest arsenal of nuclear weapons, with more than 4,300 nuclear weapons. According to SIPRI, the United States has about 3,700 nuclear weapons, and Moscow and the United States together account for 90% of the world’s nuclear arsenal.

According to the Arms Control Association, since the Trinity test, 2,055 nuclear tests have been carried out by eight countries around the world.

The United States conducted the most tests with 1,030, followed by Russia/Soviet Union with 715. France, 210; China and Great Britain, 45; North Korea has 6 people. India, 3 people. And Pakistan has two.

These experiments have taken place in locations ranging from Pacific atolls to the deserts of the United States and China to the Russian Arctic, often at great cost to human and environmental health.

Widespread nuclear testing ceased in the late 1990s, and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test Ban Treaty began to be signed.

The agreement has never entered into force, largely because the United States signed but did not ratify it, but countries have largely complied with its terms, with the exception of North Korea, which is considered a rogue state and is under UN sanctions.

And since the 2017 test at North Korea’s Punggye-ri test site, much of the world has been watching closely as to whether Kim Jong-un will conduct another test due to his massive investment in a missile program that has given him weapons capable of reaching the U.S. mainland.

But in recent months, attention has focused on the United States and Russia after President Trump and then Russian leader Vladimir Putin threatened to resume nuclear testing in their countries.

The United States last tested a nuclear weapon on September 23, 1992, and Russia last detonated a nuclear weapon in 1990, when it was still in the Soviet Union.

During a visit to South Korea in October, President Trump pledged to begin testing U.S. nuclear weapons “on an equal footing” with Russia and China, and said he had directed the Pentagon to immediately begin preparations for such a test.

On November 5, one week after President Trump’s announcement, President Putin ordered the Russian military to begin preparations for weapons tests.

Nuclear weapons tests are conducted to measure the impact of new advancements in bombs or to ensure that existing weapons would still work if launched.

Spaulding and other scientists argue that it’s all unnecessary. That’s because nuclear-armed states now have the technology to conduct “subcritical” experiments that can mimic the nuclear process right up to the point of detonation.

“Advanced nuclear powers are technologically well beyond the stage of exploring whether their weapons reliably detonate,” he wrote.

Any U.S. nuclear test now calls into question whether the U.S. government has been a reliable steward of its vast nuclear arsenal, Spaulding said.

“While the Trump administration may view nuclear testing as contributing to deterrence, it actually anticipates an irreconcilable lack of confidence in the U.S. stockpile, which could be counterproductive,” he said.

The impending expiration of the 2011 Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (START), which limits the number of nuclear warheads that the United States and Russia can deploy to 1,550, has further heightened fears of another nuclear test.

A report released this week by the Union of Concerned Scientists says that number could rise rapidly after February 5.

“Within weeks, the United States could deploy 480 more nuclear weapons at bomber bases. Within months, it could put nearly 1,000 more nuclear warheads on submarines. And within a few years, it could put 400 more nuclear warheads on land-based missiles. Russia could do the same, increasing the risk of political tensions and potentially causing serious and catastrophic miscalculations,” UCS said.

“Both Russia and the United States already have enough nuclear weapons to destroy each other over and over again. Adding more nuclear weapons increases the likelihood of an accident and increases the consequences of miscalculation and escalation,” said report author Jennifer Knox, a policy and research analyst at UCS.

START has remained unstable since President Putin suspended Russia’s participation in 2023. One reason for this is the United States’ support for Ukraine in the wake of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of its neighbor.

The Russian government suspended authorization for verification testing, and the United States followed suit.

However, Russian leaders last September proposed extending compliance with START restrictions by one year beyond February 5th.

But President Trump appears intent on letting it expire.

“If it’s expired, it’s expired,” he said. “We’re going to get a better deal,” he told the New York Times earlier this month, suggesting that any new deal should include China.

So in this record week, there is more anxiety than celebration among those who closely monitor nuclear proliferation.

“The world has quietly broken its record for the longest period without a nuclear test, but it is clear that this stability is fragile,” UCS’s Spalding wrote.