caracas, venezuela

—

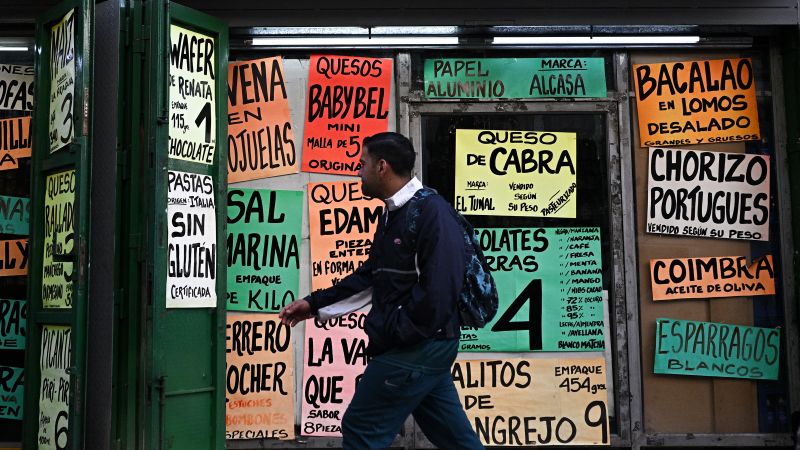

As Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro demands his resignation in the face of increasing military pressure from the United States, an old enemy is once again trying to harass him in his own backyard. Inflation, one of Venezuela’s chronic economic ills, is rising again.

“Prices are going up every day,” said Yon Michael Hernandez, 25, a motorcycle taxi driver in Petare, a shantytown east of Caracas.

“Today corn flour costs 220 bolivars, tomorrow it might cost 240 bolivars, the day after tomorrow it might cost 260 bolivars. The same package that might have cost $1 15 days ago is now worth three bolivars,” Hernandez told CNN. He mentioned Venezuela’s currency and the cooked flour used to make arepas (the ubiquitous corn pancakes), an everyday staple.

In the three months since the Pentagon sent warships and planes in an operation the White House announced targeted drug traffickers from Venezuela, the bolivar has depreciated by about 70% against the U.S. dollar, losing one point each day, according to central bank data.

The black market for illegal but widely used currencies continues to experience similarly steep declines. At the official rate, the US dollar is pegged at approximately 231 Venezuelan bolivars. On the black market, a dollar is worth about a third. The Venezuelan government prohibits publishing black market exchange rates.

The spike in inflation is partly linked to rising tensions between the Trump administration and the Maduro regime, which has been under U.S. Treasury sanctions for almost a decade.

President Maduro has accused the United States of seeking to oust him after more than 12 years in power and a year after he claimed victory in a controversial presidential election that many international observers accused of fraud.

A military strike on Venezuelan soil may not materialize, but the economic outlook is once again in the red after policy changes brought the country a much-needed economic recovery in the years immediately following the coronavirus pandemic.

Just last year, President Maduro boasted of the results of these reforms, claiming his country’s GDP had grown by 8% and inflation was at its lowest in 40 years. Autocratic leaders no longer make such claims.

According to the United Nations, Venezuela has historically not produced enough food to meet demand, requiring many products to be imported from abroad and paid for in foreign currency.

This also means that the market is particularly at risk when the value of the bolivar falls.

For many Venezuelans still reeling from years of hyperinflation before the pandemic lockdown, the new price increases are reviving a familiar nightmare.

“There aren’t many people shopping these days,” said Marjorie Yanez, 40, a street food vendor in Caracas. “They can buy as little as possible.” “The dollar is getting stronger every day, which is bad for retailers like us because we have to raise our prices every day.”

A typical breakfast of croissant and cafe con leche now easily costs $8 to $10 at a bakery in Caracas, but the country’s official minimum wage is less than $1 a month.

The flow of remittances from relatives abroad is also lacking, as more than 7 million Venezuelans fled the country in search of better opportunities under Maduro’s regime.

“I’ve had to increase the monthly allowance I send to my parents, but it’s still not enough. They can barely get by,” said Diego Mejias, 35, an architect from neighboring Colombia who supports his parents in Caracas.

Although the central bank stopped publishing inflation reports last October, the country was able to keep inflation in single digits for 20 consecutive months.

Soon after, things started to unravel.

In July, Venezuelan security forces briefly detained several economists, including former Finance Minister Rodrigo Cabezas, for sharing pessimistic views. The Home Secretary said their comments were destabilizing. Critics called the arrests baseless.

The economists were later released, but publishing economic statistics remains taboo.

For this report, CNN spoke to two private consultants with access to reliable economic data. Both spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of government retaliation.

CNN has also reached out to Delcy Rodríguez, Venezuela’s vice president for finance, and is awaiting a response.

Both consultants estimated that Caracas’ inflation rate is currently hovering between 20% and 30% a month and is destined to continue rising as long as the bolivar remains weak.

In regions outside the capital, such as Tachira and Zuria, near the Colombian border, prices are slightly lower and more imports end up in Venezuela.

In the face of the economic downturn, the government has cracked down on the black market in US dollars. In June, Attorney General Tarek William Saab announced the detention of 58 people on charges of “exchange rate manipulation.” Authorities also seized more than a dozen web pages advertising the sale of dollars and euros at rates different from the central bank’s official rate.

These moves have done little to halt the bolivar’s decline.

The International Monetary Fund last month estimated Venezuela’s annual inflation rate at about 270%, the highest in the world and up sharply from the 180% it estimated in April.

The outlook for 2026 is even more bleak. The IMF expects Venezuela’s inflation rate to exceed 600% by October next year.

The plummeting value of the bolivar could be partially explained by the U.S. military’s show of force as nervous Venezuelans look to buy foreign currency as a hedge against an uncertain future. But that’s just one of the reasons, consultants told CNN.

U.S. sanctions on Venezuela’s oil sector, the country’s biggest source of foreign exchange, are also partly to blame.

In July, the Trump administration renegotiated a permit that would allow U.S. oil giant Chevron to export Venezuelan crude oil. Under the terms of the new license, Chevron will be authorized to pay Venezuela fees and royalties in oil rather than cash, effectively cutting Chevron’s crude oil exports from the country by half, Reuters reported.

A Chevron spokesperson said the company “operates globally in compliance with the laws and regulations that apply to our operations, as well as the sanctions framework set forth by the U.S. government, including in Venezuela.”

The change proved costly as Venezuela lost one of its few remaining legitimate sources of income. As a result, the government is now forced to sell more oil at a discount on the black market to avoid U.S. government sanctions, one Caracas economist told CNN.

To make up for the lack of revenue, the government recently allowed private companies to sell cryptocurrencies in exchange for a weaker bolivar, and exchanges are openly supported by a new cryptocurrency management regulator, the National Cryptoassets Supervision Authority, known as Sunaclip.

Last year, Reuters reported that the government was preparing to increase the use of crypto assets in oil exports to overcome US sanctions. According to specialist data aggregator Chainanaracy, Venezuela is second only to Brazil in terms of cryptocurrency adoption in Latin America.

Today, thousands of Venezuelans, ranging from corporate bankers to retirees, regularly buy US dollars on Binance, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange. It’s even common to see grocery store shoppers exchanging currency in the checkout line.

Not everyone has accepted the new normal. “Sending money to Venezuela has always been difficult,” says Mejias, a Colombian architect. “Now it’s even more confusing to understand what interest rates are good and what aren’t, and it’s even more confusing for older people like my parents.”