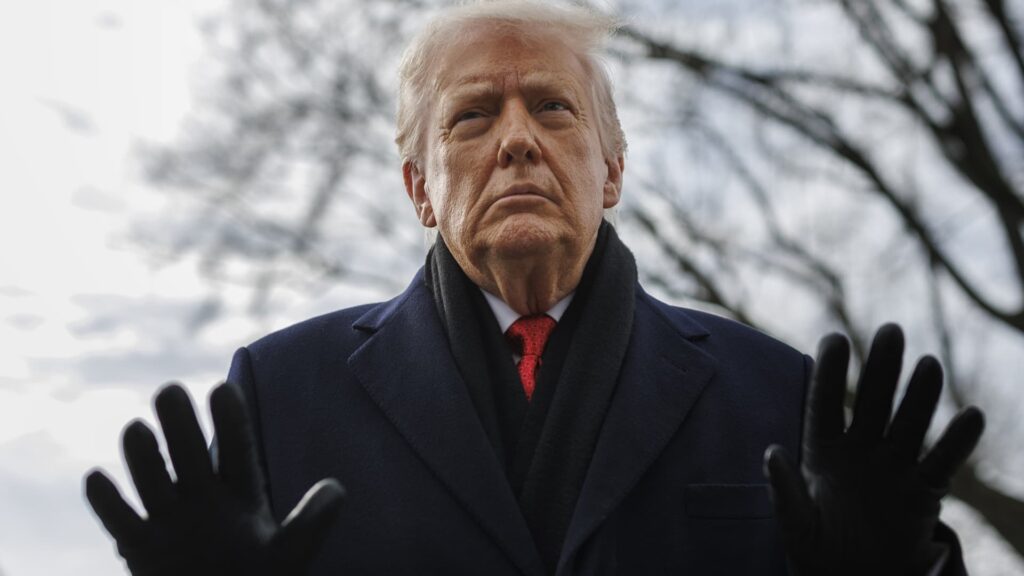

Rising political risks may be a factor in US stocks for the time being. In January, the United States attacked Venezuela, President Donald Trump attempted to annex Greenland, and threatened to impose new tariffs on eight European allies. By the end of the month, the Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier strike group was on its way to Iran after President Trump threatened a military attack on the Islamic Republic, and the president vowed to impose 100% tariffs on Canadian goods if Prime Minister Mark Carney struck a trade deal with China. The unrest strained relations between the United States and its main allies in the European Union, Britain and Canada. But for investors, there is a renewed focus on assets outside the United States in an environment that calls into question the credibility of long-standing postwar alliances. Developed and emerging market stocks alike outperformed U.S. stocks in January. While the S&P 500 index rose more than 1%, the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (EEM) rose about 8% in dollar terms and the iShares Core MSCI International Developed Markets ETF (IDEV) rose more than 4%. The iShares MSCI ACWI ex US ETF (ACWX) rose more than 5%. ‘A source of uncertainty’ Stephen Colano, chief investment officer at Integrated Partners, said of U.S. strategic policy: “It’s just a huge source of uncertainty.” “Not only do we potentially recognize it from a risk premium perspective, but I think there’s a bigger psychological risk premium in terms of trade routes and diplomacy. For at least the next three years, it’s going to be, ‘We don’t know what’s going to come out of the US next.'” Asset managers are suddenly considering the recent EU-India free trade agreement, which European Commission President Ursula von der Leyens has called “the mother of all deals.” Germany. Meanwhile, his predecessor, former European Commission President José Manuel Barroso of Portugal, said last week that relations between the United States and Europe were at their “worst point” since the creation of NATO. “With the United States leaving NATO and pulling back from aiding our allies, we are now forced, at least figuratively, to say to other countries, ‘Okay, we’ve got to rebuild our house,'” Collano said, noting that NATO members have pledged to spend 5% of their gross domestic product on defense by 2035. Security agreements “are not going to go back to just, ‘Hey, the United States is going to take care of everyone.'” The ship has sailed. ” As a result, capital flows that were once dominated by investments within and outside the United States are being reshaped. “Now it’s starting to diversify,” said Colano, whose firm manages about $24 billion. Escape from the Greenback President Trump’s tariff threats against Greenland took a toll on US assets, including the dollar, reviving the “Sell America” trade and reviving safe-haven assets such as gold. The dollar fell more than 1% in January and is 11% below its 52-week high, but rebounded on Friday after President Trump nominated Kevin Warsh to be the next Federal Reserve Chairman. .DXY 1-Year Mountain Dollar Index, 1-Year President Trump talked about the weak dollar. When asked last week about the value of the currency, he replied, “It’s great.” The rebound caused the dollar to fall on Tuesday, its worst day since April last year. “Everything President Trump does on ICE raids, everything he does on trade, everything he does with Greenland sets the stage for increased volatility,” said Lawrence MacDonald, a former Lehman Brothers and Morgan Stanley author and author of the Bear Trap Report. Trump’s threat of Greenland tariffs ushered in a “third wave” from the dollar, after Russian assets were frozen in 2022 following the invasion of Ukraine and Trump imposed comprehensive tariffs in April 2025. The new tariffs announced by President Trump last April have caused global investors to change their view of U.S. assets, even as domestic retail investors have encouraged stocks to recover after a steep sell-off, said Dario Perkins, managing director of global macro at TS Lombard. By contrast, foreign investors are nervous about adding more dollar-denominated assets and are discussing hedging against a weaker dollar. Denmark’s insurance companies and pension funds, for example, increased their hedge ratios for U.S. dollar investments to about 74% in April 2025 from about 68% a month earlier, to nearly 62% at the start of the year, according to Denmark’s central bank. Perkins said that while there is no “mass exodus from dollar assets” at the moment, there is certainly “reluctance toward dollar exposure,” noting “a new round of hedging that has led to a weaker dollar” in the past few weeks. He said there used to be a perception that when asset managers reduced risk, “the dollar would give us an extra layer of insurance and the dollar would appreciate.” “What’s troubling for investors is that we’ve seen two instances where these correlations have broken down and actually been completely reversed.” Will it continue? Wells Fargo Investment Institute’s Paul Christopher believes geopolitical risks may remain high even after President Trump’s second term ends in January 2029. “Hedging will continue to some extent,” said the firm’s head of global investment strategy. BCA Research’s Marko Papic said the dollar’s weakness is likely to continue, leading to further diversification into “slightly cheaper” areas. Macro and geopolitical strategists prefer European, Chinese, and Japanese stocks. “The S&P 500 could absolutely crash every year, but if your currency is going to drop by double digits every year, you definitely want to be non-American,” Papic said. Investors should consider a “buy the rest of the world” trade rather than a “sell America” trade. “Pick up a dart, throw it at the map and buy those assets,” he said. Indeed, asset managers’ attitudes toward U.S. assets and volatility will change depending on their country’s integration with the United States, whether economic or military. But even between the United States and Europe, where relations are closely intertwined, recent rifts “will never fully heal,” said Matthew Ax, senior strategist for international politics and public policy at Evercore ISI. But Asian allies may have “a little more instinctive hope that this policy instability is just a passing phase.” “I don’t know if Japan’s major pension funds, which are huge international investors, would consider a ‘sell America’ deal the same way as other funds… given the long-standing security ties that exist between Japan and the United States,” he said. Yet another potential risk to how U.S. assets are viewed abroad could arise from threats to the independence of the Federal Reserve System. Aksu expects the next central bank chair could create more policy instability, raising questions about whether asset prices adequately reflect the added political risk premium. If confirmed by the Senate, Warsh, who served as head of the Federal Reserve under former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, would begin his term in May. Gold and silver prices fell sharply on Friday as markets assumed Mr. Warsh was independent of President Trump and would work to fight inflation if it flared up again. “When you combine that with the reality of the Fed transition, you have another very serious vector through which this set of concerns about U.S. political risk will somehow play out,” Ax said.