Limits of pardon power

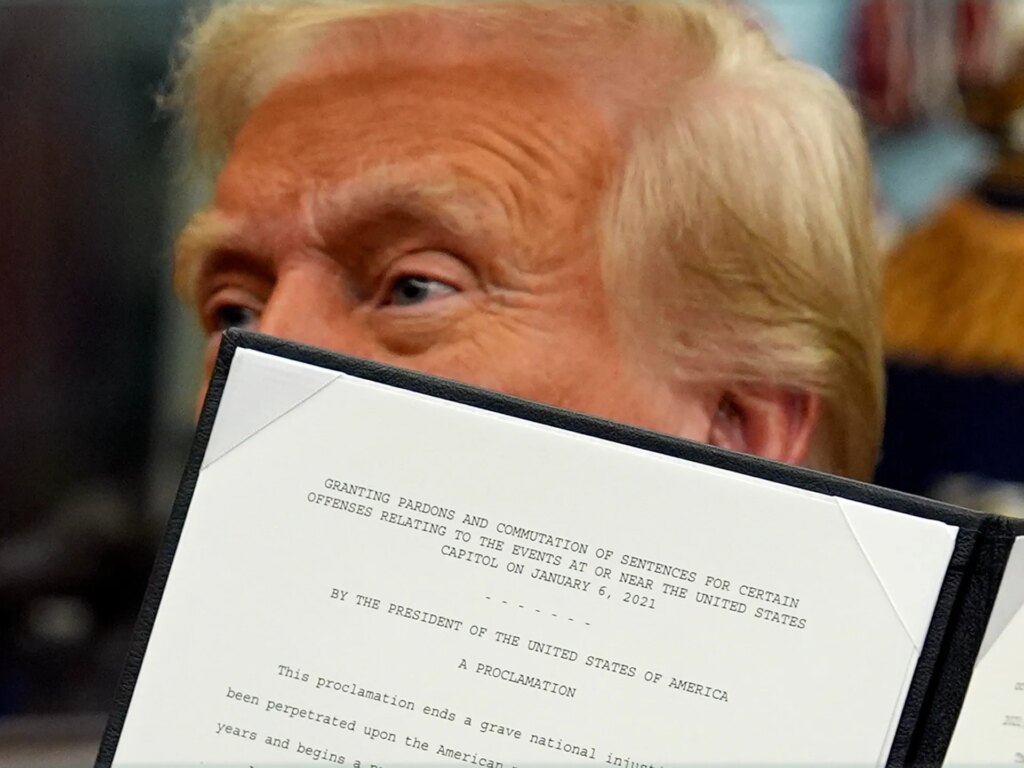

But presidential pardons have limits, and President Trump has already ignored them.

In December, President Trump announced that he would pardon Tina Peters, a former Colorado county official who supported Trump’s false claims of voter fraud in the 2020 election.

But Peters was also convicted of a state-level crime for using his office to give unauthorized persons access to the county’s election software.

The president can only pardon federal crimes, not state crimes. Peters remains serving a nine-year sentence. Still, Trump tried to pressure Colorado authorities to release her.

“She did nothing wrong,” Trump wrote on Truth Social. “If you do not release us, we will take strict measures!!!”

Trump has maintained that he has “full authority to grant pardons,” but legal experts have repeatedly argued that pardons are not without limits.

For example, pardons cannot be used to avoid impeachment or violate the Constitution. Nor can it be used to absolve future crimes.

Still, questions remain about how to enforce these limits and whether new bulwarks need to be put in place to prevent abuse.

Love points to the national pardon system as a model to emulate. For example, Delaware has a pardons commission that hears petitions at public meetings and makes recommendations to the governor. More than half of the petitions have been granted.

Like other successful amnesty programs, Love said it provides public accountability.

She measures that accountability by specific criteria. “Can people see what’s going on? Do they know what the standards are? And are the decision-makers respected and responsible decision-makers?”

But President Trump’s far-reaching actions have prompted calls to limit or completely eliminate presidential pardons.

Osler warns against doing so: It would be a “permanent solution to a temporary problem.”

“If you limit generosity, you lose all the good that comes from it,” Osler said.