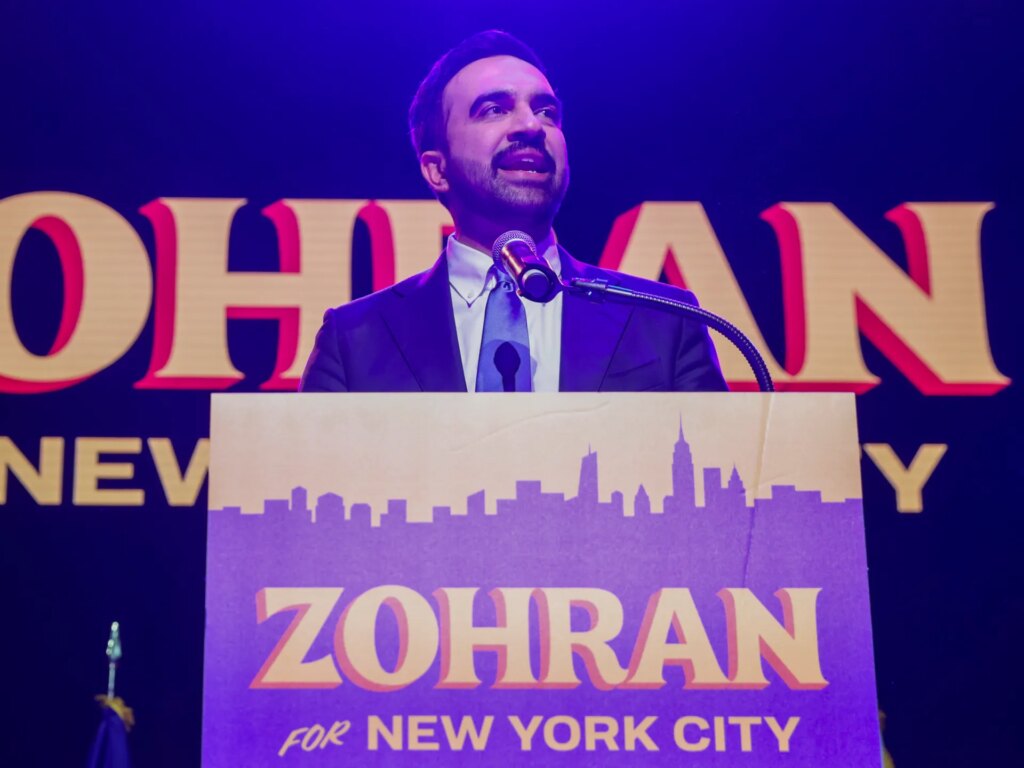

Zoran Mamdani, a 34-year-old state representative, won a surprising victory in the New York City mayoral election. Defeating former Governor Andrew Cuomo, who had strong support from President Donald Trump and the political establishment, Mamdani became the city’s first Muslim immigrant mayor and the youngest mayor in more than a century. The Democratic Socialists’ victory sent shockwaves through national politics, emboldening progressives across the country to run for office and win with an agenda as unabashedly ambitious as the moment demands.

Mr. Mamdani campaigned throughout the city, reaching out to a variety of social groups, including African Americans, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, East Africans, and South Asians, especially young people, many of whom were disengaged from politics due to the Democratic Party’s dispiriting performance in recent years. He drew people back into the political process and mobilized voters who might otherwise have stayed home.

Operating on a platform that calls for a more equitable distribution of wealth through higher taxes on the ultra-rich, a more affordable and accessible housing market, a free and faster public bus system, and universal free child care for children from six weeks to five years old, Mamdani has brought a political discourse centered on equity into the mainstream, something this country has perhaps not seen since early 20th century socialist organizer and five-time presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs. He championed workers’ rights and economic justice.

When asked on live television what he meant by “democratic socialist”, Mamdani answered: “When we talk about our politics, I call myself a democratic socialist in many ways, but that term is inspired by what Dr. (Martin Luther) King (Jr.) said decades ago: ‘Call it democracy or call it democratic socialism. There has to be a better distribution of wealth for all of God’s children in this country.'”

But what actually is “democratic socialism”? For many, the word “socialism” brings to mind the economic system of the former Soviet Union, characterized by inefficient allocation of resources, state control and ownership of productive assets, and political repression under a brutal totalitarian regime. But that’s not what socialism means.

As the late Eric Olin Wright, one of the most influential sociologists of the past half-century and a pioneer in class analysis of capitalism, detailed, the Soviet Union practiced “statism” rather than socialism, an economic system in which statism controlled investment and production through centralized planning institutions. In fact, in common parlance, most people use the term “socialism” to describe what is most accurately called statism.

Over the past century, the struggle for more egalitarian alternatives to capitalism has been waged under the banner of “socialism.” However, the term itself has long been controversial, and its precise meaning is the subject of intense debate both within and outside of academic and policy circles.

Above all, Karl Marx himself believed that socialism was based on two important principles. First, it democratized not only political life, which refers to the procedural democracy practiced in most developed countries, but also economic life, requiring ordinary workers to have a say in how economic resources are distributed. Second, socialism envisioned shorter working hours, allowing people to develop their creative abilities outside of the workplace. In fact, Marx’s critique of capitalism derives primarily from his belief that capitalism stifles “human flourishing and self-realization.”

But the socialist experiments that took place around the world in the 19th and 20th centuries bore no resemblance to these humanistic ideals. Socialism, once seen as an economic system that extended democracy into areas that capitalism would never allow, turned both economy and society into a centralized, grossly inefficient, authoritarian command and control apparatus. A Soviet-style dictatorship, rife with corruption and prostitution, turned socialism into a means of state control rather than human liberation. With shortages, rationing, and long lines at stores, by the 1980s socialism came to be seen as a failed social change project wherever it was implemented.

So what is “democratic socialism”?

This term consists of two words: “democracy” and “socialism”. Democracy is basically a socialist principle. In fact, democracy is the most effective political mechanism we know for ensuring that the state acts as an agent of the people. If “democracy” is a term that means the subordination of state power to popular power, “socialism” is a term that means the subordination of economic power to popular power. In democratic socialism, the control of investment and production is organized by truly democratic means. A central moral objective of democratic socialism is that the national economy should be organized in such a way that it responds to the needs and aspirations of ordinary people rather than to the needs of elites.

Democratic socialism thus represents an attempt to reconcile the egalitarian goals of socialism with the institutions of liberal democracy. It envisions an economy in which the market still allocates resources, but where the ownership of productive assets and the distribution of wealth are subject to participatory and democratic decision-making. The goal is not to abolish markets, but to make them responsive to the voice of the people and ensure that economic outcomes reflect shared values rather than private power.

It is now well understood that capitalism provides prosperity for some and impoverishes many others. It denies the conditions for true human flourishing and development from vast segments of the world’s population, even in the most advanced economies. “Freedom of choice” is often extolled by defenders of capitalism as its central moral virtue, but in reality it is only a partial one. The gross inequalities of income, wealth, and opportunity that capitalism produces narrow what we might call “true freedom”—the true ability of people to pursue life plans and act on the choices that truly matter to them.

The promise of democratic socialism is not just greater equality, but greater freedom. Its goal is to give all people the ability to truly shape their lives. That is what Zoran Mamdani’s platform represents. His policies, such as rent freezes, free bus fares, and universal child care, are more than just economic measures. They are instruments of true freedom for ordinary people. If most of your salary goes towards rent, your freedom will be restricted. Housing stability gives people a sense of security, helps them plan for the long term, and avoids the stress of possible eviction. Housing stability is tied to human dignity. Fare-free public transport gives you greater freedom of movement throughout the city. Free buses make mobility a right rather than a privilege, opening up the physical and social space of freedom itself. And universal childcare frees parents, especially women, from the impossible trade-off between childcare and social participation. When society shares the burden of childcare, everyone has equal freedom to work, learn, and participate in social life. These policies redefine freedom not as the privilege of a few with unlimited accumulation, but as the ability shared by all to live with security, opportunity, and power over their lives. That is the freedom that democracy promises, and that is the freedom that democratic socialism delivers.

Among today’s capitalist countries, the social democracy of the Nordic countries (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland) is closest to the ideals of democratic socialism. The insistence on a much stronger working class and a resolute commitment to social welfare over the narrow interests of elites has long distinguished these countries from other types of capitalism. However, despite a more even distribution of income in social democracies than in other parts of the developed world, wealth inequality remains significantly higher.

Mamdani’s election as mayor of New York is a ray of hope that the democratic process can still serve the many, not the few. Once dismissed as naive, his equity-centered platform has won the trust of a diverse majority who yearn for justice and dignity. This victory, achieved in the face of relentless racism and Islamophobia, represents a collective victory.

But the election is just the beginning. The hard work ahead is to translate promises into policy and hopes into concrete change for a more humane and equal distribution of economic resources. people spoke. Now it’s delivery time.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.