Monterrey, Mexico – In April, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum announced that the country’s aerospace industry could continue to grow by up to 15 percent annually over the next four years, attributing the sector’s expansion to a robust local manufacturing workforce, rising exports and a strong presence of foreign companies.

However, with the impending review of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the trilateral free trade agreement that has supported the growth and prosperity of Mexico’s aerospace industry, the industry’s future is now uncertain.

Recommended stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

Stakeholders have warned that ensuring investment stability and strengthening labor standards are essential to protecting the sector’s North American supply chain.

Mexico strives to be among the top 10 countries in terms of aerospace production. This is a goal outlined in Plan Mexico, the country’s strategic initiative to strengthen its global competitiveness in key sectors.

As the sixth-largest supplier of aerospace parts to the United States, the industry has benefited greatly from the USMCA, which has fostered regional supply chain integration, said Monica Lugo, director of institutional relations at consulting firm Prodensa.

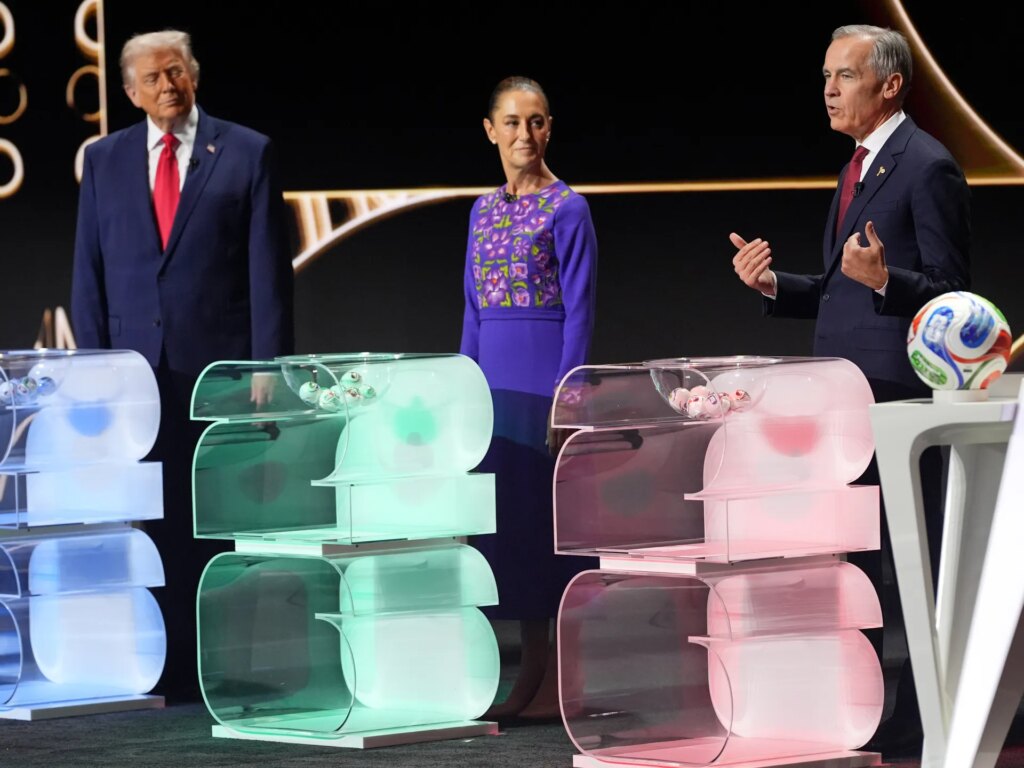

But the combination is no guarantee the business will continue to grow, as the U.S. is in “unprecedented times” with President Donald Trump and his expansive tariff policies.

Lugo, a former USMCA negotiator, said recent tariffs on materials such as steel and aluminum that are critical to the aerospace industry have undermined the United States’ credibility as a reliable partner. She predicts that the sector risks losing capital, investment and jobs if current conditions continue.

“There’s great uncertainty that one day it’s on, the next day it’s off, and tomorrow nobody knows, and acting based on the president’s mood rather than specific criteria creates chaos and seriously damages the country and the economy,” she said.

On December 4, President Trump indicated that the United States could allow USMCA to expire next year or negotiate a new agreement. This follows comments from U.S. Trade Representative Jamison Greer to U.S. news outlet Politico that the administration is considering separate agreements with Canada and Mexico.

Rapidly growing aerospace field

Citing data from the Mexican Federation of Aerospace Industries (FEMIA), Sheinbaum said Mexico’s aerospace market is valued at $11.2 billion and is expected to more than double to $22.7 billion by 2029. Home to global companies such as Bombardier, Safran, Airbus and Honeywell, Mexico has established itself as a major player in the global aerospace market and is now the world’s 12th largest exporter of aerospace parts.

Marco Antonio del Prete, Secretary of Sustainable Development for the state of Queretaro, attributes this success in part to significant investments in education and training. In 2005, the provincial government of Querétaro promised Canada’s Bombardier to invest in education and establish an aviation university. The university currently offers programs ranging from technical degrees to master’s degrees in aerospace manufacturing and engineering.

“Since Bombardier’s arrival, we have created an education and training system that allows us to develop talent in a very efficient way, on a fast track, so to speak,” Del Prete told Al Jazeera.

Bombardier has served as an anchor, driving Queretaro’s rise as a highly skilled manufacturing hub for parts and components.

Initially focused on wiring harnesses, Bombardier’s factory in Queretaro has evolved to specialize in complex aerostructures, including the rear fuselage of Bombardier’s ultra-long-range business jet, the Global 7500, and key components of Bombardier’s mid-size business jet, the Challenger 3500.

Marco Antonio Carrillo, a research professor at the Autonomous University of Querétaro (UAQ), noted that the region’s extensive education has developed a strong workforce, which has attracted significant attention from aircraft manufacturers, mainly from the United States, Canada and France.

“This development (of Queretaro) was really explosive from a time perspective,” Carrillo said.

Mexico also aims to join France and the United States in becoming the third country to fully assemble engines for Safran.

But the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM) union, which represents more than 600,000 workers in Canada and the United States, is concerned that advances could eventually lead to more advanced manufacturing and assembly work moving to Mexico, given investments in local aviation universities and training.

“Right now they[Mexican workers]are doing more entry-level jobs, but our concern is that in the future a larger portion of aerospace business will go to Mexico,” Peter Greenberg, IAM’s international director, told Al Jazeera.

High-skilled, low-cost workforce

Among the three countries that have concluded the USMCA agreement, Mexico’s biggest attraction is its low-cost manufacturing.

Edgar Buendia and Mario Duran Bustamante, economics professors at Rosario Castellanos National University, point to Mexico’s low labor costs and geographic proximity to the United States as its main advantages. This is part of the reason why the United States, including during the first USMCA negotiations in 2017, has increased pressure on the Mexican government to raise wages to level the playing field and reduce unfair competition.

“Given (low) wages and geographical location, most US companies have an incentive to move production to Mexico. So to prevent that, the US is asking Mexico to raise labor standards, ensure freedom of association and improve working conditions,” Buendia told Al Jazeera. This would benefit Mexican workers, despite concerns from employer-led labor groups that Mexican workers would lose their advantages.

IAM initially opposed NAFTA, the USMCA’s predecessor. Greenberg acknowledged that the USMCA will continue, but said U.S. and Canadian workers “will probably be completely satisfied” once the deal ends, as the NAFTA deal has shuttered factories and laid off workers as jobs are moved from the U.S. and Canada to lower-cost Mexico.

“We need stronger incentives to keep jobs in the U.S. and Canada. We want wages to rise in Mexico so that it doesn’t become an automatic place for companies to take advantage of workers who have lower wages and who don’t have bargaining power or strong organization,” Greenberg added.

Under Mr. Sheinbaum’s Morena party, Mexico raised its minimum wage from 88 pesos ($4.82) in 2018 to 278.8 pesos ($15.30) in 2025, bringing the minimum wage in municipalities bordering the United States to 419.88 pesos ($23). On December 4, Sheinbaum announced a 13% minimum wage increase, with a 5% increase in border areas starting in January 2026.

Despite these increases and the competitiveness of wages in the aerospace sector, researchers agree that a large pay gap still exists between Mexican workers and those in the United States and Canada.

“The pay gap is definitely egregious,” said Javier Salinas, a scholar at the UAQ Labor Center who specializes in labor relations in the aerospace industry. “The average in the (aerospace) industry is 402 (Mexican pesos) to 606 pesos, with a maximum daily wage of 815 pesos. (But) if you convert 815 pesos to U.S. dollars, a working day is less than $40.”

By contrast, Salinas estimates that the average daily income of workers in the United States is about 5,500 pesos, or $300.

“Protection Association”

The USMCA called on Mexico to end “protection unions,” the long-standing practice in which companies sign agreements with corrupt union leaders known as “syndicatos charros” without workers’ knowledge. The system has been used to discourage genuine union organizing, as these syndicates often serve the interests of companies and government officials rather than workers.

Salinas argues that despite the 2019 labor reforms, the emergence of independent unions remains difficult. Meanwhile, “protection unions” continue to keep wages low to maintain competitiveness.

“But imagine, you have a competitive advantage based on precarious or poor working conditions. I don’t think that’s the way forward,” Salinas said.

Even with new labor courts and laws requiring collective bargaining, organizing in Mexico remains dangerous. Workers who try to form independent unions often face dismissal, intimidation, or being blacklisted by their companies.

Humberto Huytron, a lawyer specializing in collective labor law and trade unionism, explains that workers in Mexico, including in the aerospace sector, often lack effective representation. “There is discrimination in hiring and recruitment. We do not hire workers who have been fired for union activity,” he said.

In addition to calling on Mexico to implement labor reforms, IAM is also calling for the expansion and strengthening of the Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM), which allows the United States to take countermeasures when factories do not uphold freedom of association and collective bargaining rights.

Although not in the aerospace sector, the United States recently invoked RRM against wine producers in Queretaro. Previous such measures in the state were limited to the automotive sector.

“No one knows exactly what’s going on in all the factories in Mexico,” Greenberg said.

According to FEMIA, 386 aerospace companies operate in 19 states. These include 370 specialized factories generating 50,000 direct jobs and 190,000 indirect jobs.

However, Del Prete assured Al Jazeera that the union is independent in Querétaro and “has its own organization.”

Salinas pointed out that Queretaro hasn’t had a strike in decades, adding: “Imagine the management of the workforce. There hasn’t been a strike in the private sector for 29, 30 years.”