U.S. authorities have announced that the measles outbreak in the southern state of South Carolina has increased by nine since the beginning of this week to 185.

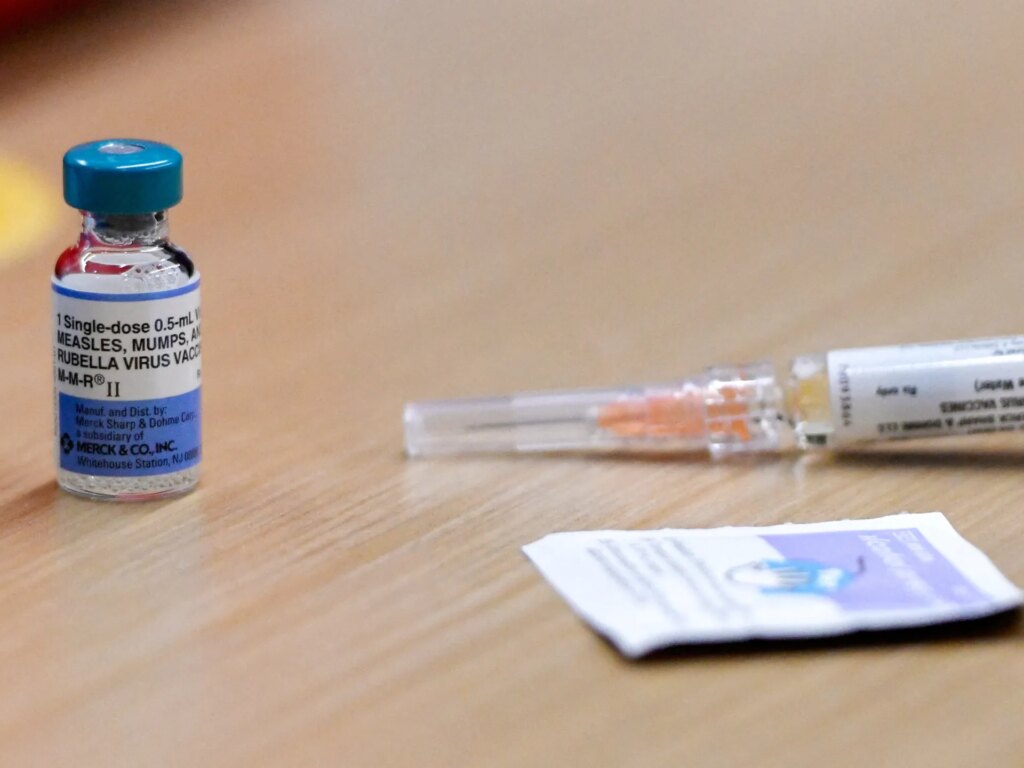

In Friday’s update, state officials specified that 172 of the cases involved patients who had not received the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine designed to prevent infection.

Recommended stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

Four other cases involve partially vaccinated patients, four have unknown vaccination status, and four more are still under investigation. Only one of the infections involved a fully vaccinated person.

Measles, a highly contagious and sometimes deadly virus, was declared eliminated in the United States more than 25 years ago. But over the past year, that position has become increasingly difficult to maintain.

Typically, a disease is declared eradicated if there is no local transmission in a particular region, but cases can still be “imported” from abroad.

The US eradication status is largely due to the success of the MMR vaccine.

The first measles vaccine was licensed in the United States in 1963, and by 1971 a combination MMR vaccine was introduced that protects against three diseases at once. Two doses are usually recommended to achieve full vaccination status.

Originally, in 1978, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set a 1982 deadline to achieve measles elimination in the country. It fell short of this goal for nearly 18 years, reaching defeated status in 2000.

But vaccine hesitancy was blamed then and now for allowing the virus to spread in the United States.

Measles has a relatively low mortality rate, but the infection rate is high. The CDC estimates that when one person contracts the virus, they can infect nine out of 10 people around them.

The World Health Organization says there are about two to three deaths for every 1,000 reported infections.

Children are particularly vulnerable. Complications may include high fever, loss of hearing or vision, and encephalitis, which is inflammation of the brain.

Health professionals typically recommend that children be vaccinated early in life, with the first dose by 15 months of age and the second dose by age 6. Vaccines are widely accepted to be safe.

But skepticism about the vaccine is growing in the United States, with critics partly blaming policies implemented under President Donald Trump’s administration.

According to CDC data, the MMR vaccination rate for U.S. kindergarteners was 95.2% in the 2019-2020 school year.

But that number will drop to 92.7 percent by the 2023-2024 school year, a difference of 280,000 kindergarteners.

The year 2025 represented a high water mark in the resurgence of measles virus. The CDC reported 2,065 measles cases last year, the most since 1991 and more than seven times the number in 2024, when only 285 measles cases were reported.

One of the largest outbreaks occurred in Texas, where three people died from the virus and was first reported in February last year. Prior to this incident, no measles deaths had been reported in the United States since 2015.

Following the deaths, President Trump’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., encouraged people to get vaccinated, writing on social media that “the MMR vaccine is the most effective way to prevent the spread of measles.”

But Kennedy, who is not a medical expert, has since expressed views that appear to discourage the use of the vaccine.

For example, in late April, he told NewsNation, “The MMR vaccine contains large amounts of aborted fetal fragments and DNA particles.”

However, experts denounced that claim as false. The rubella portion of the vaccine was developed using cell cultures obtained from elective abortions in the 1960s, but no fetal tissue has been used since then, and the vaccine is also free of fetal issues.

President Kennedy also promoted unsubstantiated claims linking vaccinations to autism, despite widespread protests from the medical community.

In South Carolina, the current measles outbreak is concentrated in the northwest. The South Carolina Department of Public Health says the reported cases are primarily children under the age of 17.

Pediatrician Annie Andrews, one of the Democratic candidates running in the state’s 2026 midterm elections, has made combating the spread of infection a central focus of her campaign. She wants to unseat incumbent Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham on the November ballot.

“If you had told me while I was in medical school that one day I would be running for the Senate and my campaign slogan would be ‘measles or me,’ I definitely would not have believed you,” she wrote on social media on Friday.