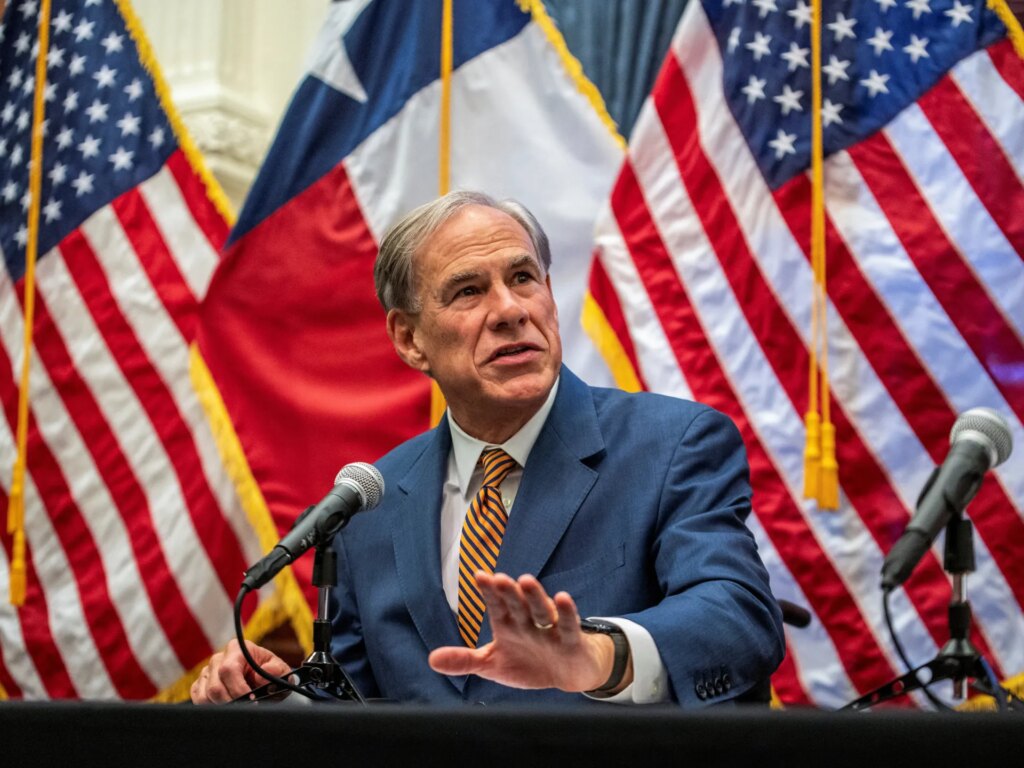

When Texas Governor Greg Abbott called for a formal investigation into the so-called “Sharia court” on November 19, it was not based on evidence, charges, or any legal wrongdoing. It was a political performance. There are no Sharia courts in Texas, only Islamic voluntary arbitration boards that operate under the same framework as the Jewish Beth Din courts and Christian arbitration services.

But in a letter to district attorneys and sheriffs requesting an investigation, Abbott said, “The Constitution’s religious protections do not empower religious courts to circumvent state and federal law simply by donning robes and expressing positions contrary to Western civilization,” suggesting that Muslims are secretly creating an alternative legal system.

This is not a law enforcement agency. It is political theater aimed at inciting fear.

The day before, on November 18, President Abbott issued an executive order designating the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), the nation’s largest Muslim civil rights organization, as a “foreign terrorist organization” (FTO).

The order cited no criminal record, no violence, no conspiracy, and no prosecution record. It was simply a broad assertion that American civil rights groups constituted a national security threat.

Lawyers quickly pointed out that Abbott did not have the authority to designate an FTO. Only the U.S. federal government does that. But again, it’s not the legal accuracy that matters.

This ineffective order was intended more as a political message than anything else. The goal was to portray Muslim Americans and their organizations as suspects and their civil activities as security risks.

Mr. Abbott’s actions are the latest product of a long-running American panic machine that turns ordinary Muslim lives into a narrative of threat. This panic machine has been operating for decades and has repeatedly weaponized Islamic law for political gain.

For example, in the late 2000s, a nationally organized campaign led by activists like David Elsalmi and groups like ACT for America urged lawmakers across the country to introduce “anti-Sharia” legislation. In the early 2010s, more than 40 states considered legislation that would prohibit courts from applying “foreign law” (a euphemism widely understood to mean Islamic law).

The most extreme example occurred in the US state of Oklahoma, where voters approved a constitutional amendment explicitly banning the application of Islamic and international law. When the law was challenged in court, a federal judge blocked it.

This case and other legal challenges have exposed these measures as political stunts rather than responses to real legal issues. But the broader campaign succeeded in normalizing the idea that Muslim religious practice itself is a national security threat, paving the way for subsequent escalations, including today’s Abbott actions in Texas.

The calls for an investigation into “Islamic courts” come months after another Muslim-led real estate project in Texas became the subject of a Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation and was branded an “Islamic court” online. Local residents were told that Islamic law would govern the area, that non-Muslims would be excluded, and that the development was part of a creeping Islamic takeover. None of the rumors were true. The project was open to everyone and aimed solely at addressing the region’s housing crisis.

The Department of Justice closed its investigation in June, finding no illegality, but in September Governor Abbott signed a law banning “Islamic compounds” in Texas.

This dynamic extends far beyond Texas. In Tennessee, opponents of the Murfreesboro mosque argued that Islam is not a religion and therefore Muslims do not deserve First Amendment protection. This argument went against centuries of constitutional principles, but that didn’t matter. The key was to make Muslim religious life appear legally illegal.

In Dearborn, Michigan, one of the oldest cities in the country with Arab and Muslim communities, a false rumor has repeatedly spread that the city has been “taken over by Islamic law.” Fabricated videos, manipulated headlines, and images from other countries have been disseminated to create the illusion of Islamic rule on American soil. Although fact-checking has revealed these stories to be false, the rumors persist.

Muslim celebrities have also been targeted. During his campaign, New York City’s next mayor, Zoran Mamdani, faced racist memes and conspiracy theories claiming he plans to introduce “Islamic law” if elected. Mamdani’s policy proposals have no religious content. His agenda focuses on public transportation, housing, and police accountability. But for those obsessed with Islamic law panic, Muslims in public office are always considered a Trojan horse.

And it’s not just Republicans who have fanned the flames. Mainstream newspapers, liberal politicians, and even civil liberties organizations have repeatedly adopted the underlying framework that Islamic law is inherently alien, inherently political, or inherently antithetical to American values. By accepting the premise that Sharia is a threat, you effectively legitimize the Islamophobic narrative structure, even if you claim to be against Islamophobia.

These incidents reveal a consistent pattern. The panic over Sharia is not about law, security, or constitutional principles. It is about maintaining boundaries in a country suffering from demographic change. It’s about who counts as an American, and who remains forever in doubt. Panic continues to resurface not because it reflects legitimate concerns, but because it is useful as a tool to mobilize voters, police citizens’ sense of belonging, and justify state surveillance.

What makes this all the more ironic is that Sharia, as it has been understood by Islamic scholars for centuries, bears little resemblance to the caricatures that animate American politics. In Arabic, Sharia means “path to water” and is a metaphor for moral and spiritual nourishment.

It is a broad ethical framework about justice, welfare, and accountability. Its fundamental purpose, Maqasid al-Sharia, revolves around the protection of life, intelligence, faith, property, and human dignity. This tradition includes sophisticated doctrines of equity (istiḥsān), public interest (maṣlaḥa), and custom (ʿurf), which closely resemble the fair and circumstantial tools of modern common law systems.

Far from being an exotic legal code, Sharia shares deep structural resonances with Western legal traditions. As Professor John Makdisi demonstrated in his groundbreaking North Carolina Law Review article, some basic features of English common law are strikingly similar to the Islamic legal system that supposedly came through Norman Sicily. This history is important not because it collapses distinctions between legal systems, but because it exposes the absurdity of the idea that Islamic law is inherently incompatible with Western governance.

America once understood its heritage. When the Supreme Court chamber was unveiled in 1935, it was decorated with a marble frieze depicting mankind’s great lawgivers, including the Prophet Muhammad, holding the Koran as a symbol of justice and moral authority. Today, acknowledging that simple historical fact would itself provoke outrage.

A new Sharia panic does not mean Islam is entering American courts. It’s about Islam permeating American civic life. It is about Muslim political participation, Muslim community development, Muslim institutions, and Muslim representation, all of which are being reframed as existential threats. As the country enters a new election cycle fueled by anti-diversity rhetoric, anti-Muslim conspiracy theories, and attacks on Middle East studies programs, sharia has become a flexible receptacle for a much older anxiety: fear of a pluralistic America.

It is not Sharia that is dangerous. What is dangerous is a political machine that turns ordinary Muslim Americans into objects of suspicion, targets of state power, and instruments of culture wars they did not choose. If there’s anything Americans should fear, it’s not Islamic law but the weaponization of fear.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.