Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro appears further isolated this week after losing two regional allies, Honduras and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, in votes to counter Washington’s naval buildup in the Caribbean.

In Honduras, preliminary results from Sunday’s election made one thing clear. Candidate Rixie Moncada, a protégé of leftist President Xiomara Castro, had little chance of winning the presidential election, dropping to a distant third place.

While votes are still being counted, the race has narrowed down to two right-wing candidates: Salvador Nasrallah, who has pledged to sever ties with the Venezuelan government, and Nasry Asfura, who US President Donald Trump endorsed last week.

In Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves, an ardent supporter of President Maduro, lost an election last week after nearly 25 years in power. The country will now be led by centre-right politician Godwin Friday, whose party won 14 of the 15 seats in parliament.

These results, combined with previous political changes across Latin America, indicate the region is moving away from the once popular populist movement in Venezuela known as Chavismo. It was founded by President Hugo Chávez, who died in 2013, and was succeeded by President Maduro.

Even countries ruled by left-wing or centre-left leaders, such as Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Colombia, have restricted relations with President Maduro’s Venezuela, especially after the contentious 2024 election. Mr. Maduro was declared the winner of re-election despite evidence to the contrary.

changing landscape

Countries in the region have oscillated between left-wing and right-wing leaders, although Venezuela remains largely in the same position after more than 25 years of Chavismo rule.

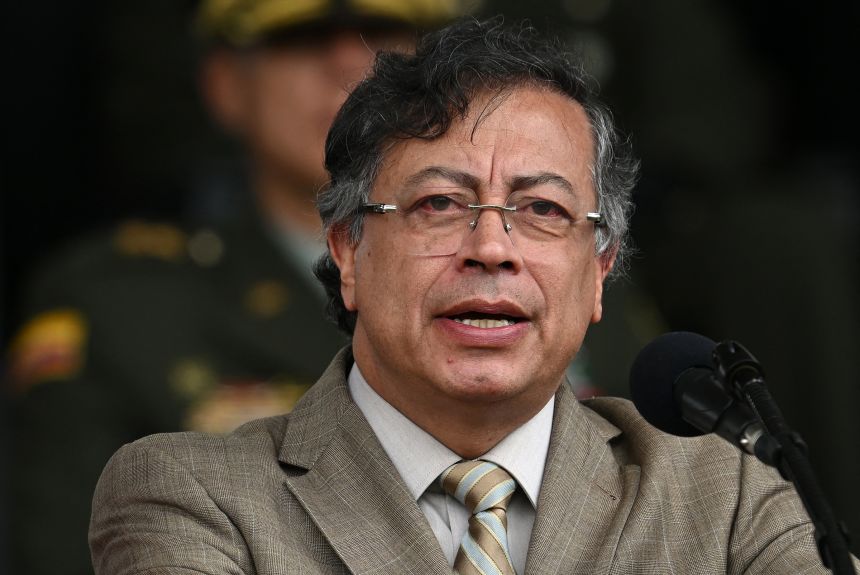

Colombia has a long land border with Venezuela and has a problem with cross-border drug trafficking, but relations with the neighboring country have always been unstable. Under current President Gustavo Petro, that partnership has become unstable.

Petro re-established diplomatic relations with the Venezuelan government during the early days of his admiration, but now appears to be distancing himself from its leader. Petro told CNN last week that Maduro has nothing to do with drug trafficking, as the United States claims, but acknowledged that the Venezuelan president’s problem is a “lack of democracy and dialogue.”

Relations between Venezuela and Argentina deteriorated over time. Under the left-wing presidency of Néstor Kirchner (2003-2007) and his wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007-2015), Caracas and Buenos Aires saw an increase in trade and aid, and diplomatic relations were restored. But dialogue was effectively cut off after center-right businessman Mauricio Macri was elected president in 2015, and further cut off after Javier Millay, a self-proclaimed liberal who hates socialism, was elected president in 2023.

Other Latin American countries, including Ecuador, El Salvador and Bolivia, have also moved to the right and away from Maduro in recent years.

Relations with Brazil range from friendly to hostile. Relations with Caracas flourished during the left-wing governments of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010) and Dilma Rousseff (2010-2016), but deteriorated during the right-wing governments of Michel Temer and Trump’s far-right ally Jair Bolsonaro. When Lula da Silva returned to office three years ago, relations improved, although they were not at the same level.

If the situation in the Caribbean escalates into a larger conflict, Venezuela has only a handful of friends left in the region, none of which are likely to be of any use.

Cuba, a longtime adversary of the United States, has been a staunch ally of Venezuela since Chavez came to power, and remains so to this day.

Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez told CNN in late September that Cuba had “full and complete support” for the Venezuelan government. However, when asked if Cuba would respond to a U.S. attack on the country, the foreign minister avoided a direct answer, saying, “That’s a hypothetical scenario. If we receive word that there is a U.S. military intervention, we will let you know.”

The communist-battered island is experiencing one of the biggest economic crises in recent memory, but is in no position to provide military aid to Venezuela, and beyond Rodriguez’s statements, Cuba remains on the sidelines.

Another friend of Venezuela is Nicaragua, a small Central American nation led by Daniel Ortega. The controversial president has long been accused of human rights abuses, allegations he strongly rejects.

Mr. Ortega has been largely silent during this tense period, offering no aid to Venezuela. But in late September, he denounced the U.S. military buildup in the Caribbean, claiming the U.S. government was trying to “seize Venezuela’s oil by fabricating a story that the cocaine came from the south.”

With President Maduro increasingly isolated in Latin America and his old friends preoccupied with their own problems, it is extremely difficult to predict the impact of a potential conflict in a region that has long had a love-hate relationship with the United States.

The Pentagon has sent more than a dozen warships and 15,000 troops to the region as part of an operation dubbed “Operation Southern Spear,” and President Trump held a meeting at the White House on Monday night about next steps against Venezuela, sources familiar with the matter told CNN.

On Sunday, President Maduro responded to the U.S. pressure campaign with a familiar, defiant message: “There were sanctions, threats, blockades, economic war, but Venezuelans did not flinch. Here, as the saying goes, everyone put on their boots and went to work.”

Since succeeding Chavez as president in 2013, Maduro has become accustomed to living hand-to-mouth, especially amid a number of major crises that have led him to tighten his grip on power, people who have worked directly with him told CNN.

“He is preparing a series of negotiations and will not part with the cards in his deck unless forced to do so,” a diplomat in Caracas told CNN last month, requesting anonymity because of the confidentiality of the conversations.

It’s a tactic honed from years on the picket line, and means Mr. Maduro, a former union leader, is effectively betting that the White House is bluffing. Venezuela’s leaders are well aware that public opinion in the United States, especially Trump’s supporters, has very little appetite for foreign intervention.