In the weeks since Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro was captured by the US military, the world’s attention has focused on who is best placed to rule the country after 13 years under dictatorship.

Since Maduro’s unceremonious ouster at the hands of US special forces on January 3, his right to succeed has been claimed by: Delcy Rodriguez, Maduro’s former deputy, is now acting president with the apparent support of US President Donald Trump. Trump himself has previously claimed to be “in charge” of Venezuela. Venezuela’s opposition leader Maria Colina Machado said last month that her coalition should lead the country. Machado won the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize after fighting through a chaotic election that propelled him to the top of President Maduro’s most wanted list.

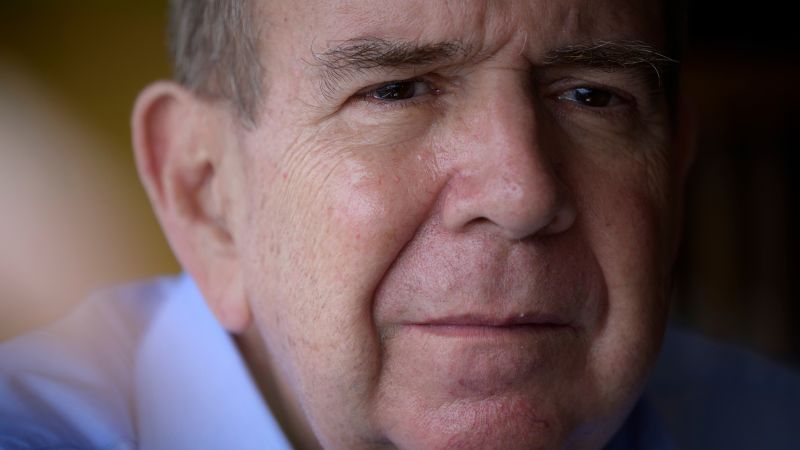

But one important voice is missing from center stage. That’s Edmundo González Urrutia, the man who replaced Machado in the 2024 presidential election after he was banned from entering the country and, according to both the opposition and several Western countries, including the United States, actually won the vote.

Since that disputed election, Machado’s international profile has skyrocketed. This is thanks not only to her daring escape from Venezuela while traveling to Norway to accept the Nobel Prize, but also for her subsequent presentation of the award to Trump when she met him at the White House in January. She is someone who has been in direct dialogue with U.S. officials as the opposition seeks to secure its position in post-Maduro Venezuela.

Meanwhile, Mr. González has rarely been seen in public. So what happened to him?

González, who has been living in exile in Spain since late 2024, has remained largely silent since the U.S. operation to oust President Maduro. The day after the attack, while Machado was still silent, he issued a statement calling this moment “an important step, but not enough” and calling for the release of political prisoners.

Since then, he has not said much about the transition of power in Venezuela, instead focusing on the release of these prisoners. This was an issue close to Maduro’s heart, as his son-in-law Rafael Tudares was arrested during Maduro’s presidency and sentenced to 30 years in prison by Venezuelan authorities.

After Tudares was released along with dozens of other political prisoners on Rodriguez’s orders in what the Venezuelan government said was a gesture of “peace,” González made one of his few public comments on the 2024 elections in an interview with Fox Noticias, in which he said: “More than 7 million Venezuelans voted for our candidates. Given that reality, the process of democratic normalization in Venezuela must proceed.” Please start. ”

That aside, he has been a man of few words since the election – in fact, he always has been.

A former diplomat who served as Venezuela’s ambassador to Algeria and Argentina, he is far more accustomed to negotiating behind the scenes. In fact, he was not the first, second, or even third choice of the opposition coalition known as the Democratic Unity Platform. After Maduro’s government shut out Machado, both academic Corina Joris and former presidential candidate Manuel Rosales were considered as potential replacements.

Mr. González was the last resort for the opposition to submit ballots within the election deadline.

“The fact that he was so low profile was actually a very positive thing for the opposition, and that’s why he was chosen because he was less polarizing and he was much less likely to be blocked,” said Rebecca Bill Chavez, president and CEO of the Inter-American Dialogue. “That was a quality that helped the opposition. But it’s also one of the reasons why he’s less relevant today.”

Those close to Mr. González know that, as he has repeatedly admitted, he never really wanted the presidency. In late April 2024, shortly after his candidacy was officially announced, he told Venezuelan media: “I never imagined that I would be in this situation.”

Shortly after the comment, a portrait by Bloomberg photographer Gaby Oraa of feeding a colorful wild macaw, known in Venezuela as a guacamaya, went viral. And the last hope for the opposition quickly became a beloved grandfatherly image for voters.

Experts say there is a political strategy behind Mr. González’s continued stay on the sidelines. “Political movements generally tend to project one clear political voice, and right now that’s Machado,” Chavez said.

“The fact that she won the Nobel Prize is a big deal. At the same time, I think it’s important to recognize that he’s a central figure in the democratic legitimacy of the opposition. He’s the one who holds the electoral power.”

That mindset is probably why Machado uses “we” so often in his remarks, but it’s not enough to stop some voters from wondering why they’re hearing so little from the man they consider the true president-elect.

And it’s not just that González is so quiet, even the main players sometimes act as if he doesn’t exist. Let’s take Trump as an example. The US president has a lot to say about Rodriguez and Machado, from claiming that the Nobel laureates are not “respected” enough to hold power in Venezuela to saying in late January that he was considering involving Venezuelan rebels “in some way” in the country’s leadership.

But President Trump has remained surprisingly quiet about González, and it remains unclear what the next steps in Venezuela’s transition will be. In an interview with NBC News published on February 12, Rodriguez said Venezuela would hold “fair and free” elections, but did not provide a timeline.

González himself appears to want to stay out of the spotlight, but that choice comes at a price.

“The opposition has basically been divided into two groups for about 20 years. The essential difference has been strategic, not ideological,” Phil Ganzon, a Venezuela analyst at the International Crisis Group who has lived in Caracas for more than 20 years and knows González personally, told CNN.

Hardliners like Machado believe in more aggressive political action, such as mass mobilizations and protests, and have low confidence in elections, while moderates like Gonzalez are inclined to exploit every political opening that exists, including elections.

“Politically, Edmundo is a moderate. He is not part of the same faction of the opposition as (Machado),” Ganzon said. The relationship became even more complicated after González went into exile and Machado went into hiding after the 2024 vote.

“She’s the one making all the decisions. She’s the one giving the orders. She’s the one making the statements. And often she’s making statements in her name, or in the names of both of them, and he finds out about it after these statements come out,” Ganson said. “Her political style is quite authoritarian.”

Ganzón, who was González’s neighbor, said Machado preferred to leave all decisions to her and her inner circle. “And[González]is just not part of the inner circle,” he told CNN.

In Washington, where Mr. Machado is well known on both sides of the political spectrum, both Mr. Machado and Mr. González are listed on Venezuela’s official information center. “They claim to represent him, but they don’t. They haven’t consulted him,” Ganson said.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world in Madrid, González is surrounded by many Venezuelan exiles seeking more active political action. “His position is not comfortable,” Ganson said. “He’s geographically isolated from decision-making. He’s just kind of trapped in what (Machado) says.”

For Ganson, that dynamic is unlikely to change. González found himself quietly playing the role assigned to him as someone who never really wanted the presidency in the first place: a figurehead role that lends legitimacy to the opposition.

“We should look at this as a sacrifice he made because he felt it was his duty to do it,” Ganson said.

“But even now, he probably wouldn’t dream of becoming president.”